ATLANTA — John Lewis spent his entire adult life fighting for justice and equality. He had the courage to risk his life to promote change.

His fight for equal rights began with lunch counter sit-ins as a teenager, then joining the Freedom Riders, where he was often brutally beaten.

Years later, after fighting for years in the civil rights movement, Lewis never stopped that fight, becoming a veteran lawmaker in Washington, D.C.

He would represent Georgia's 5th District in the House of Representatives for 17 terms -- from 1987 until his death on July 17.

His determination would be tested but never broken. He spent 15 years as a lawmaker attempting to pass a piece of legislation of personal importance.

In 1988, Lewis began pushing for construction of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. During the 15-year fight though, he was continuously met with opposition.

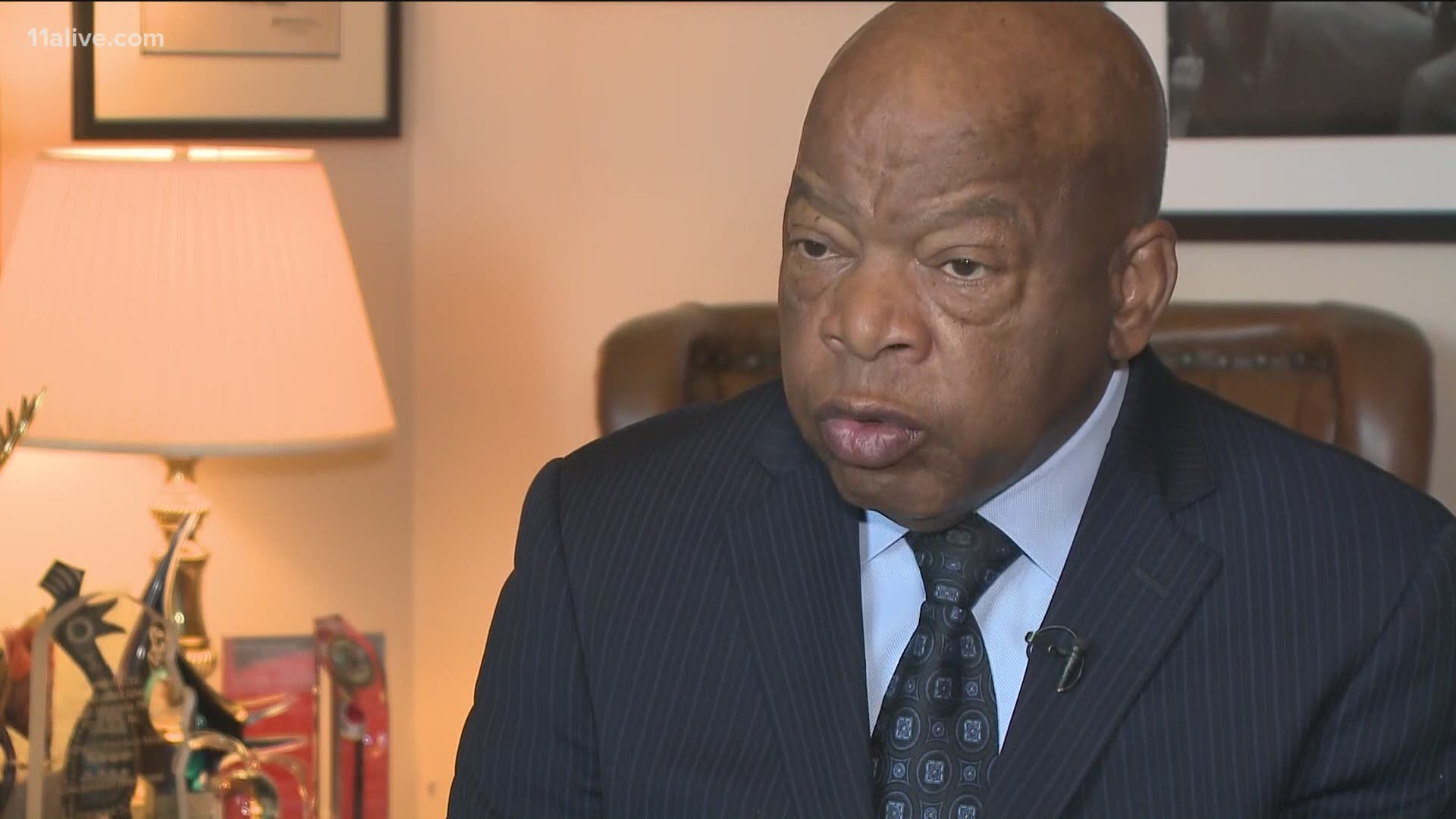

"Very hard, very difficult, almost impossible for us to get it through the Senate because of one Senator, by the name of Jesse Helms from the state of North Carolina," Lewis told 11Alive in a 2016 interview. "He didn't want to see an African American museum on the (National) Mall. I insist that it must be on the Mall. I called the Mall the 'front porch' of America. It should be near the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument."

Lewis' bill would finally pass Congress and be signed into law in 2003. It took another 13 years before the museum would be built and opened. He called the 2016 opening a dream come true and told 11Alive he had to fight back tears.

"We must tell the story, the whole story, 400-year story of African American contribution to this nation's history," Lewis said about the museum. "From slavery to the present. Without anger or apology."

Part of that history includes that of the civil rights movement -- a movement Lewis will forever be tied to.

His longtime colleague in Washington, House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer of Maryland said Lewis brought his fight for civil rights to Washington.

In a statement, Hoyer wrote on Saturday, "(Lewis) worked to secure the victories of the Civil Rights Movement by strengthening the laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s and building on them today."

While the bill behind the museum was perhaps the most important bill to Lewis that he authored, he called the vote on the 2010 Affordable Health Care Act, which he voted in favor of, a defining moment for lawmakers.

"This may be the most important vote that we cast as members of this body. We have a moral obligation today, tonight to make health care a right and not a privilege," Lewis said during a 2010 speech from the House floor ahead of the ACA vote. "At this hour, stand with the American people and not with the big insurance company."

Lewis would often use the term 'good trouble' to describe his role in the civil rights movement. He said it was a type of necessary trouble himself and others used in the 1960s as they pushed for voting rights and to end segregation.

Even in Congress, Lewis continued to cause good trouble.

"Give us a vote! Let us vote! We came here to do our job. We came here to work," Lewis shouted during a 2016 speech on the House floor following the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida.

Lewis and other Democratic lawmakers were demanding the Republican-controlled House of Representatives hold a vote on bills aimed at curbing access to guns.

"We have to occupy the floor of the house until there is action," Lewis said before leading a sit-in on the floor along with a few dozen other lawmakers.

Then Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin), called the move a publicity stunt.

Lewis responded in an interview with 11Alive saying stunts can sway the American opinion.

"The tactics and techniques that we used in the 60s as still fresh, still smart," Lewis commented.

A sit-in was a sometimes effective technique Lewis used decades earlier when he risked his own safety while leading the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 60s as it attempted to end racial segregation in the South.

Lewis' good trouble also extended to fighting for civil and human rights on the international stage.

The Georgia lawmaker would be arrested outside the Sudanese Embassy in D.C. in 2006 and again in 2009. Officers led Lews away in handcuffs along with other lawmakers after they blocked the entrance to the embassy.

Lewis was protesting actions by Sudan's government, the genocide in Darfur, and the withholding of aid to refugees.

Despite his concern for the rights of everyone, no matter their nationality, Lewis in 2016 spoke during a press conference and used his role as a congressman to say there was still more work to be done here at home.

"The scars and stains of racism is deeply embedded in society and I think what is happening is that we cannot sweep it under the rug in some dark corner, we have to deal with it. All of us. Members of Congress. Local Government. The religious community. But I have hope and faith that we will get there," he said.

REMEMBERING JOHN LEWIS |