DENVER — As thousands of Colorado Catholics celebrate Holy Week, many of them are finding hope in Julia Greeley, a woman whose life story may convince the pope to declare her a saint.

“She never knew that she mattered. But she mattered,” said Dr. Barbara Wilcots, who sat on an Archdiocese of Denver committee that researched Greeley’s life.

In 2016, the archdiocese opened the cause for sainthood and sent about 11,000 pages of documents to the Vatican. The Vatican is currently reviewing the case.

Wilcots, who serves as the vice president of student affairs at Regis University, expressed the importance of Greeley’s potential canonization because she is one of only six Black Americans being considered for sainthood within the Catholic Church.

“For that person to have been formerly enslaved, and to be a woman, and to be Black, I think is really important,” Wilcots said. “It really humanizes what it means to be a saint, because as we are Catholic, we are all called to be saints.”

Greeley’s story

Greeley, who was born into slavery in Missouri and was eventually emancipated, came to Colorado in the 1800s and worked as a housekeeper.

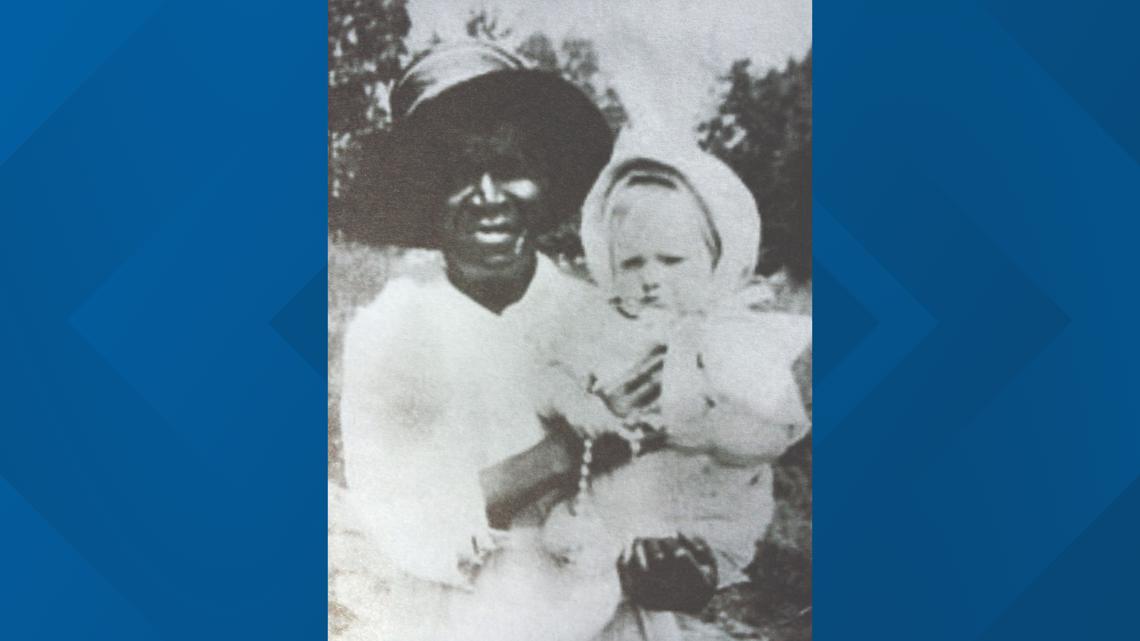

In the only photo of her in existence, her right eye appears to be closed. According to her story, a slavemaster’s whip hit Greeley’s eye while she was a baby being held in her mother’s arms.

Church records show Greeley became deeply devout to the Catholic Church after she was baptized at Denver’s Sacred Heart Catholic Church, where she was known to pray.

Greeley was known to ask for items like food, toys, coal and bedding from the families she would work for and then carry them in a red wagon throughout Denver. She would deliver goods to the needy at night, because many of them were white and didn’t want to be seen getting help from a Black woman.

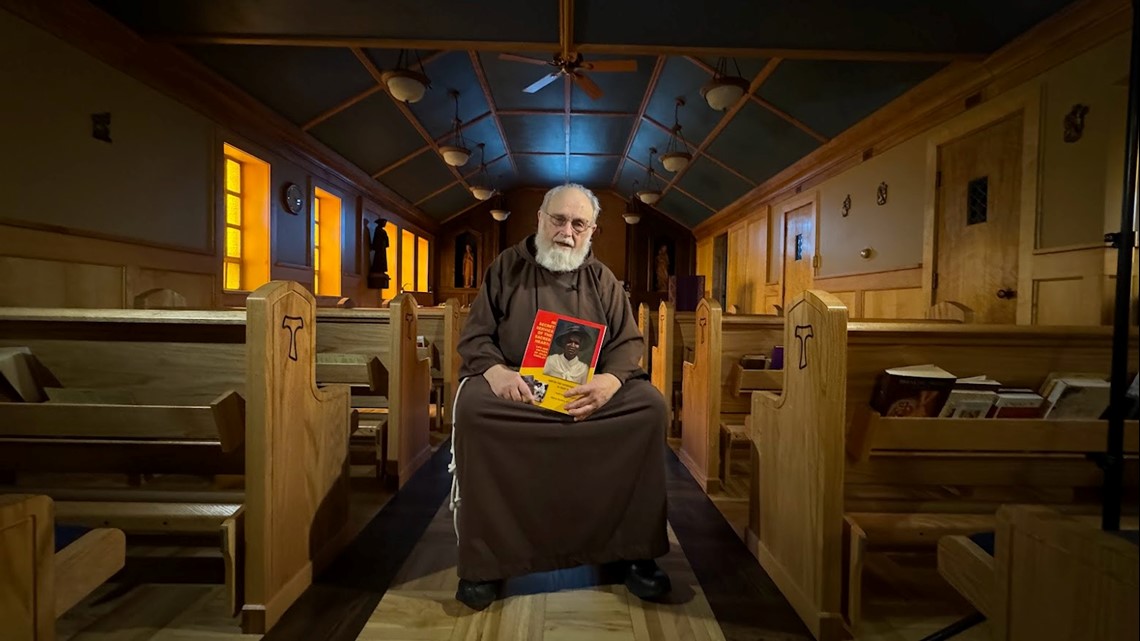

“She did it at the back door at night and tried to do it as secretly as possible,” said Rev. Blaine Burkey, who wrote a biography on Greeley.

“She had so many reasons to be bitter,” Burkey said. “She didn't spend her time taking it out on anybody. She spent it helping other people.”

“Anytime she heard there were poor people who needed something, she did what she could to try and help them,” Burkey said.

One miracle believers attribute to Greeley is the birth of a child to a family who suffered the loss of a child. The woman was told she could no longer have another baby. Greeley, who worked for the family, said a baby would come soon.

“And Julia told her, ‘Don’t worry. Pretty soon there will be a little angel running around the house.’ And in fact, not long after that, the woman found out she was going to have a child,” Wilcots said.

The child can be seen in the only photo of Greeley that exists.

Because of the story of the miracle child, Burkey said he has received notes and letters from people around the world who struggled to have children. The parents said Greeley had given them hope, and some reported conception.

“Once her cause was opened, that became worldwide,” Burkey said of Greeley’s growing fame.

When Greeley died in 1918, local newspapers reported thousands of people in Denver came to see her body because of her reputation of being devoted to the church and the needy.

Soon after the Denver Archdiocese opened a cause for sainthood in 2016, Greeley’s remains were exhumed at Mount Olivet Cemetery and transferred to the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception in Denver.

From 2018: Julia Greeley's tomb gets a new home

Today, visitors to the basilica can see a large marble sarcophagus with Greely’s name carved into the stone, which also displays the symbol of the Sacred Heart.

A forensic anthropologist found Greeley’s bones were riddled with arthritis. Wilcots said it’s likely Greeley experienced discomfort and pain when she walked the streets of Denver at night to help the needy.

“She put her own pain and her own personal affliction aside, and just to see that someone has the capacity, it makes your own affliction seem less of a concern,” Wilcots said.

The time frame on when the Vatican will make a decision on Greeley’s sainthood is unknown, but historically it can take decades for the pope to canonize someone who is a candidate.

Wilcots doesn’t expect the decision to come in her lifetime, but holds hope and admiration for Greeley.

“When you think about someone who went about their business living the way we are called to live, caring about people, and sacrificing whatever you have, it makes the possibility of sainthood seem real,” Wilcots said.

If you have any information about this story or would like to send a news tip, you can contact jeremy@9news.com.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Colorado’s Leading Ladies