COLUMBIA, S.C. — For the first time since his mother died, Lester Young sat in his cell and cried.

"I remember getting really emotional," said Young. "I never really cried when my mom passed away, so I had all of this pain built up from that, and sentenced to life in prison and living with the guilt of that."

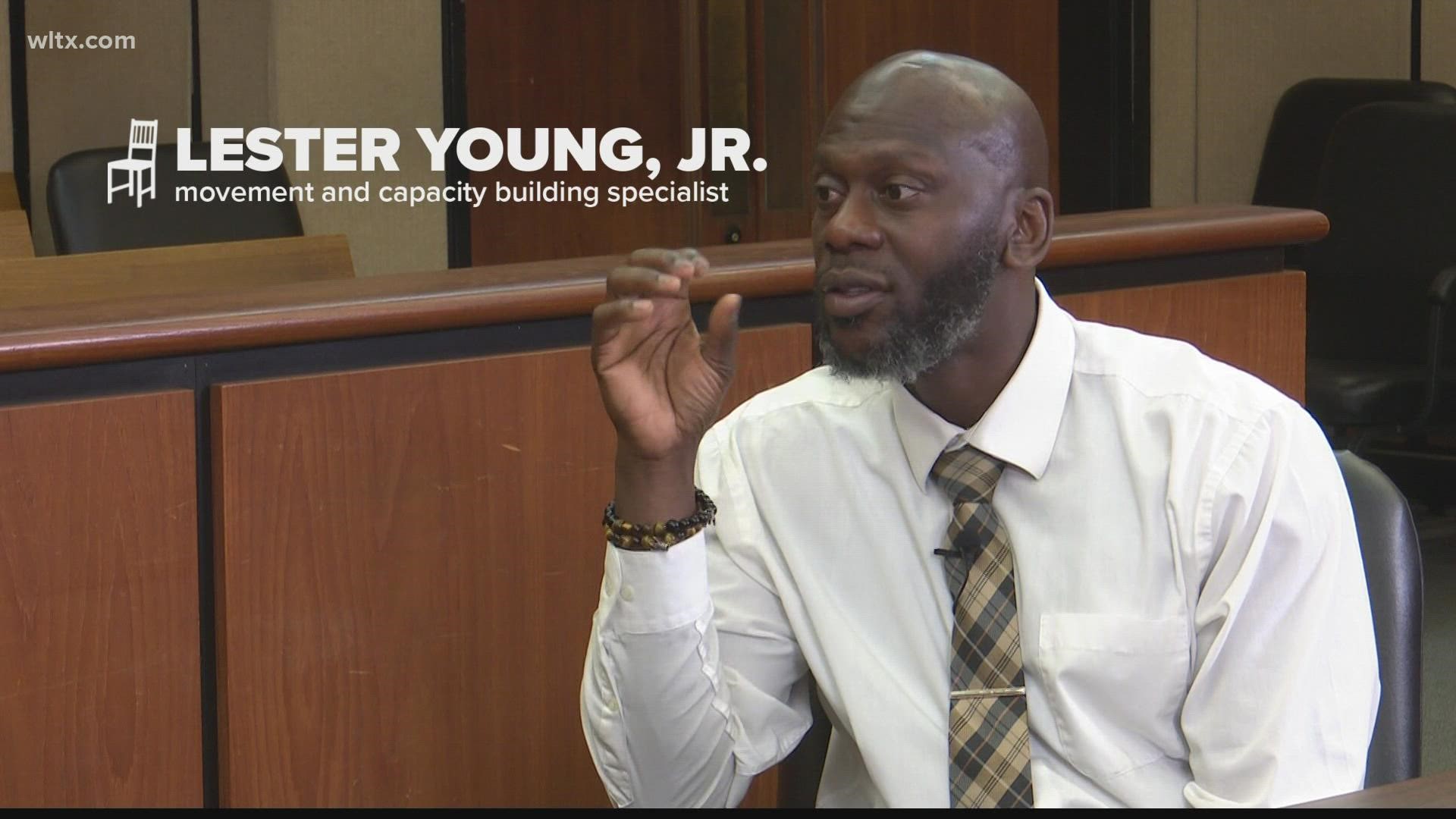

In 1991, at the age of 19, Young was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole after serving 20 years.

Young said his crime happened during a drug deal done gone bad.

He started selling drugs at the age of 16, after his mother passed away suddenly.

Young said he turned to the streets and found his identity in selling drugs and the lifestyle it could bring.

"I didn't release that pain," said Young. "It just went from anger to living with nothing to live for. I remember just being in shootouts and was not afraid to die."

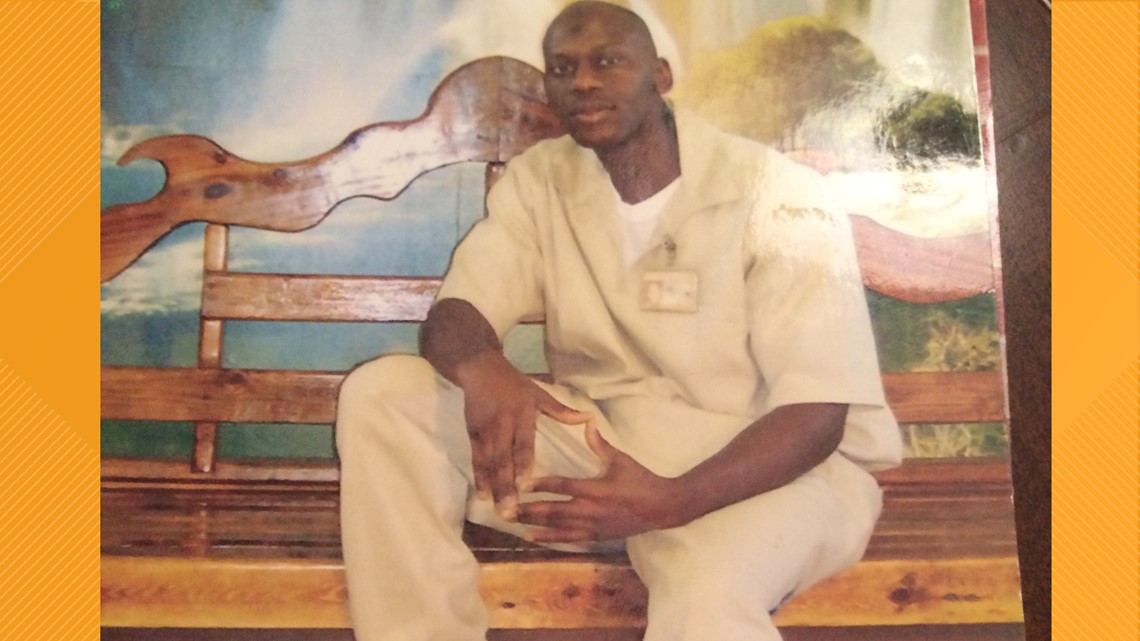

He explained that he carried that same hurt and anger with him to Allendale Correctional Institution where he was sent to serve out his sentence.

"I was struggling with the fact that I killed someone over drugs, and I had no one to talk to," said Young.

But in 1996, the night he finally released the tears and emotions that he suppressed for years, Young says the spirit of the man he killed appeared in his cell while he was in prayer.

He says God put it on his heart to speak directly to his victim. In that moment he promised his victim, "I'm going to do everything, as long as I have life in my body, to honor your soul."

"Second thing, I remember watching Oprah Winfrey Show, and she mentioned this thing about gratitude journals," said Young.

This was a major marker in his rehabilitation journey because it inspired him to start journaling. "I have over 35 journals," Young said. "And in these journals, I started writing letters to myself to the family, to my family, to my victim, to God. And that's when I begin that process of understanding that my life has to change, and it will change."

Young also credits his dad for his personal transformation, explaining that his father would visit him every weekend, place a Bible on the table and say, "Son, you have to find something greater to believe in...and you have to use this as an opportunity for change."

On May 15, 2014, after serving 22 years and 5 months in prison, Lester was released on parole.

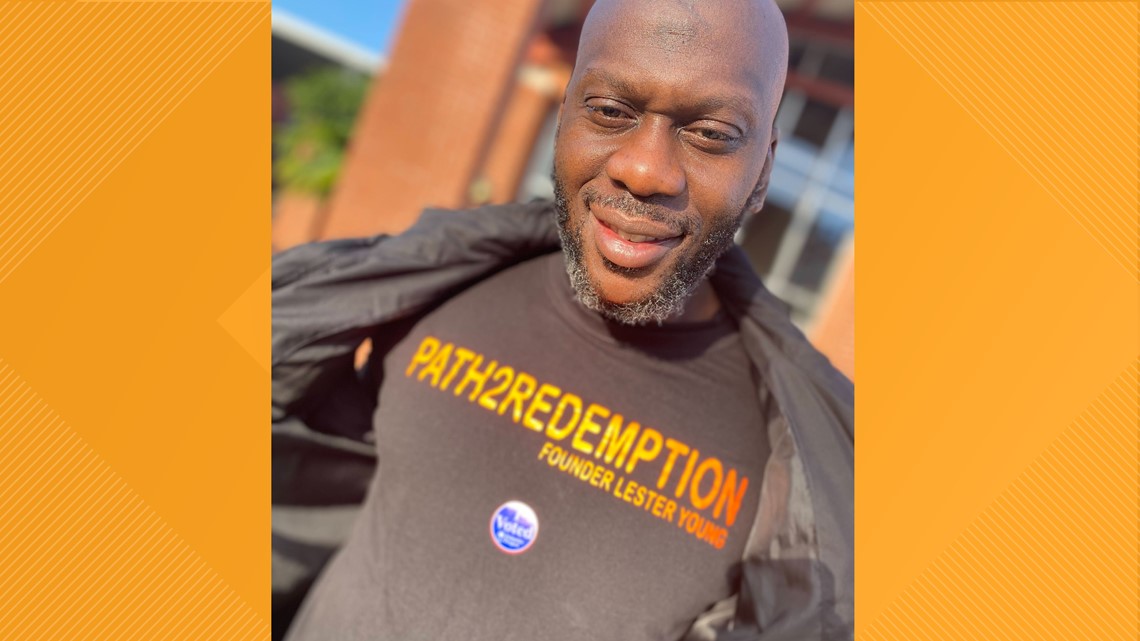

One year after his release, Young established his non-profit organization, Path2Redemption. He says the organization was a vision that God gave him after prison.

"I found that every individual in prison was searching for redemption," said Young. "And that path of redemption was connecting them to a purpose while helping them heal from the things that created that situation that they were in prison (for)."

The mission of Path2Redemption is to provide formerly incarcerated individuals a pathway of transition back into society. Young knows first-hand how challenging this transition can be. "I know what it feels like to be struggling with depression," he said, "like walking out of prison and wanting to stay in my room for days, and everybody's moving around and I cannot connect with my family members."

According to Path2Redemption's website, the organization also provides mentoring services for at-risk youth, in hopes of preventing them from entering through the pipeline to prison. The organization offers mentoring programs and workshops for the young people in our community.

Young has also been critical in making sure that previously incarcerated people have a fair chance at getting a job in the city of Columbia.

While on a flight out of Columbia, Young says he ran into Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin. He says they had a conversation about the need for the city to "Ban the Box", which refers to a nationwide effort to remove the question on the front of an application for employment that states, "Have you ever been convicted of a crime?"

Although the City of Columbia already had a policy to "Ban the Box", Young pushed for an ordinance to make it a law.

"When a company or business chooses to employ somebody who has a felony conviction, you didn't just hire him -- that person has an entire family," said Young, who struggled to land a job after his release.

"When you deprive them (formerly incarcerated individuals) of financial stability, now you're creating an unstable community," said Young. "Now you are creating a community who's going to have the ripple effect upon ripple effect, which can cause more poverty, more crime -- because there's no money circulating in a community. So when you employ and you give people opportunity for housing and rehabilitation programs, you're changing an entire community."

Young is also working with the Commission of Minority Affairs on their Second Chance Reentry Resource Guide. It provides resources to the formerly incarcerated as they transition back into society.

In addition to his non-profit organization and work with the Commission of Minority Affairs, he is also works with Just Leadership USA.

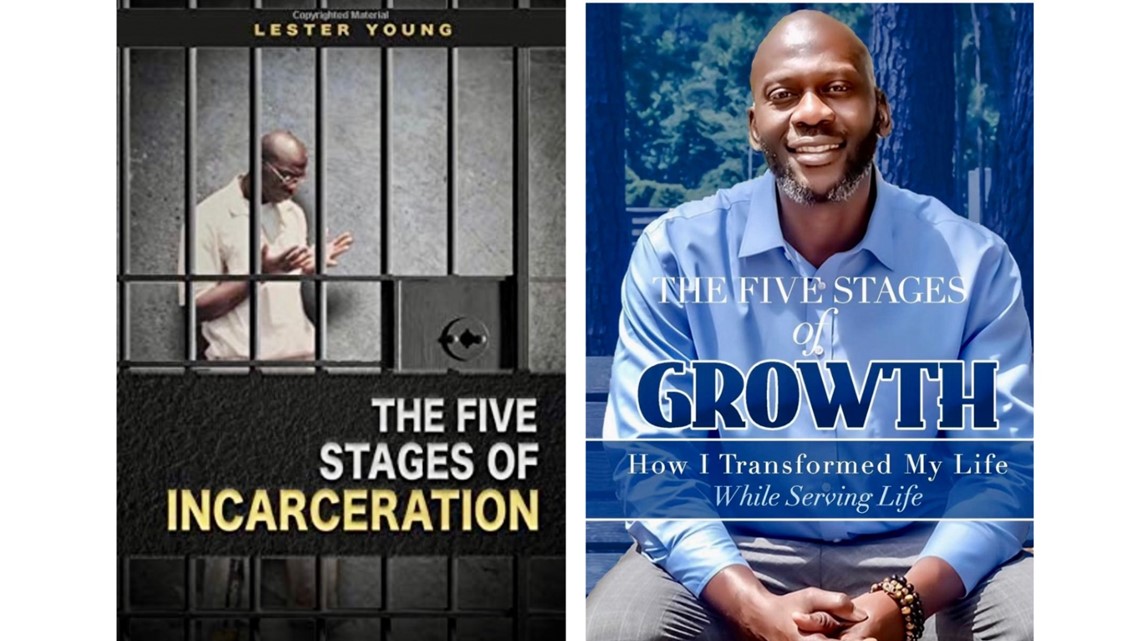

Young also created another resource for to help as those incarcerated or facing incarceration. He wrote a book called The Five Stages of Incarceration where he documents his experience in prison and his "journey to redemption." His second book, called The Five Stages of Growth, follows Young's transformation while serving his sentence and after his release.

Although Young began his focus on the individual, he also sees the need for institutional and systemic reforms -- prison reform, rehabilitation as well as better legislation and opportunities for those impacted by the criminal justice system.

Based on his experience in prison and lack of resources, Young believes corrections departments need more counselors trained in understanding trauma. "When I say laws need to be changed, (I mean) we need to do an overhaul of the complete prison system and change the whole thing of punishment to true rehabilitation," said Young. "That means addressing the holistic person, addressing the trauma (that put them there), preparing these individuals to transition back into the community and be thriving.

"Laws are not passed to hinder you from progressing forward, but allow (for new) laws that allow you to move forward in a more fluid way after your incarceration."

As a certified life coach and motivational speaker, Lester is passionate about working with at-risk youth. He stressed that its about more than behavior modification -- "understanding that they're living in trauma, it's about now approaching it through the lens of addressing and helping them heal from trauma," he explained.

Young says elected and community leaders need to look at the social factors that are shaping these children's lives.

"A young person, 12 years old, doesn't wake up and say 'I am going to kill someone today' unless they have seen it and it has been normalized," said Young. "So how do we how do we address that? We have to stop looking at it as way of writing more laws, creating more security cameras. Let's look at training more people in our community, around trauma, addressing the trauma and begin to address it that way."

While Young has accomplished a great deal after his release, he believes he still has so much more work to do. "I feel like I have to continue to live and do these things so that we can continue to change this system by inspiring people and letting them know that it's possible that a person who was convicted of murder, sold drugs, read at a 7th grade level education, could walk out of prison after 22 years and be able to create this type of momentum, and change the narrative."

Cheering, supporting and encouraging Young along the way is his wife, Filicia, who he met 7 years before he was released from prison. Together, they have a 5-year-old daughter. "That's like my anchor, my motivation," said Young. "That's my 'why' for everything that I want to do."

Currently, Young visits Lee Correctional Institution twice a week to mentor inmates. His goal is to go to share his story in every prison in South Carolina as well as Department of Juvenile Justice and teach practical reentry workshops.

He wants his story to inspire young people and those incarcerated that they can also be change-makers in their community. "You know the issue, you're the expert on the issue that is going on this community," Young said. "All you have to do is just be confident enough, get some mentorship around you to help you be able to articulate the issue, so that you can create your own table. And you can now call people to this table to explain what the issue is."

He hopes his work will also change the narrative around formerly incarcerated individuals. He believes their voice matters and can be used to create effective, long-lasting change in communities across the country.

"Those who are closest to the problem have the solution, but are furtherest away from the power and the resources," explained Young. "So because we are away from the power and the resources, we create our own table."

"Everything I'm doing now is about redemption, because the God that we all believe in, regardless of your different faith, is a God that redeems, a God of redemption," said Young.

Adam Brown assisted in the video editing of this story.

To see more of A Seat at the Table series, follow the link on wltx.com