SUMTER, S.C. — After a woman was found unresponsive and ultimately died early Wednesday morning at the Sumter-Lee Detention Center, News19 is looking at how people dealing with mental health crises are transferred to state facilities.

Law enforcement says 26-year-old Hosanna Dinkins had been at the county jail for nearly two months — without criminal charges — waiting for a bed to open at a facility.

"I just want him to get help. He's not getting it there," Cheryl Ray said, crying. "We're going backwards, not forward."

Ray says her son has been in the Sumter-Lee Detention Center since March. She didn't want to go on camera for an interview, but she wanted to share how her son is sitting in the jail, waiting for an evaluation from the South Carolina Department of Mental Health (SCDMH).

"It's made me sick to my stomach that I feel like my hands are tied. If I was a multimillionaire, I could afford all kinds of stuff," Ray said. "But like most people, we're all working day to day just to make ends meet. You want to do what you can for them."

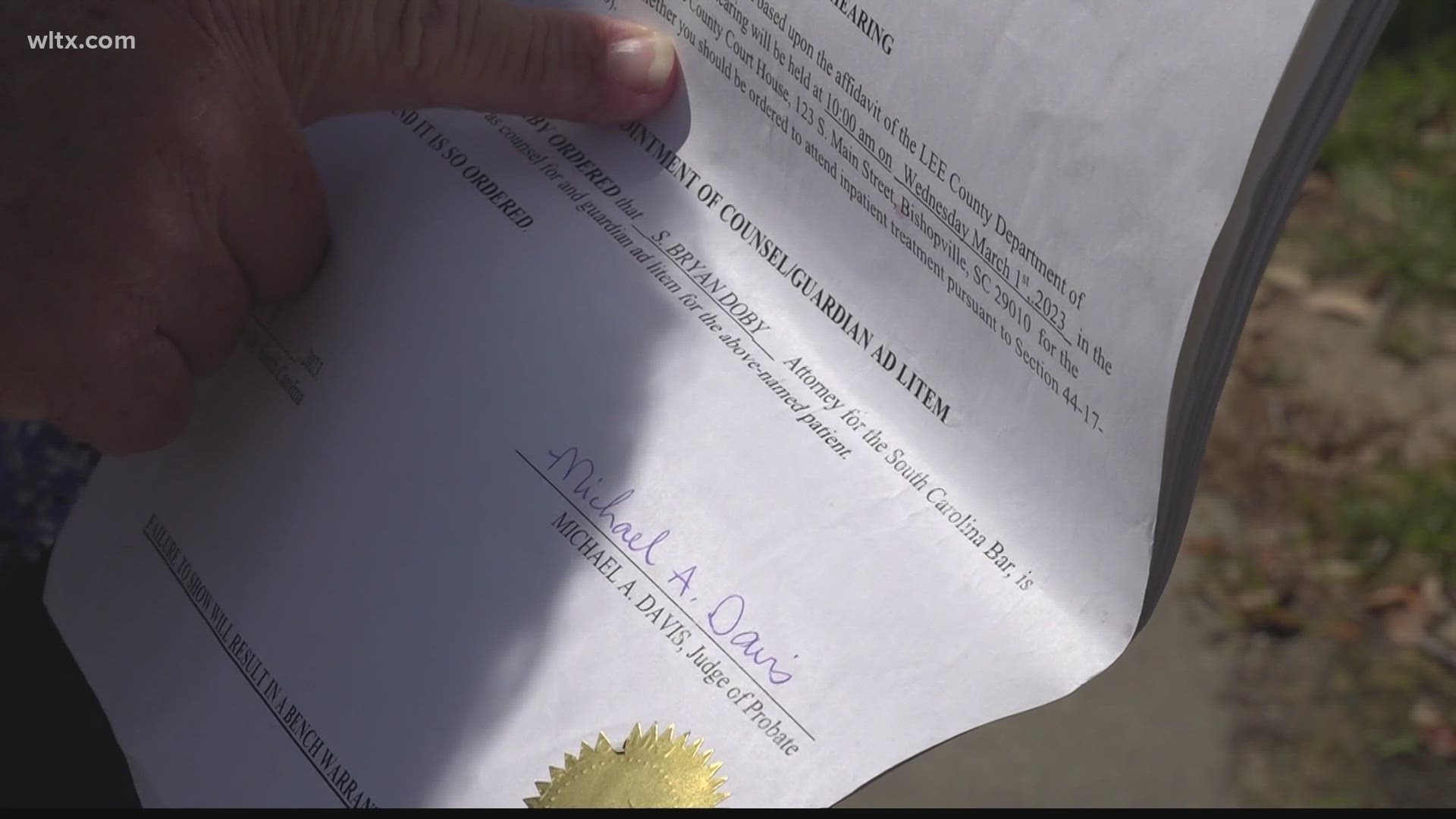

Ray said a probate judge ordered her son to be held at the jail after he failed to appear for two court-ordered mental health counseling sessions. The original order was for 90 days, but no beds became available at the SCDMH facilities, so Ray says the judge ordered another 90 days.

"The end of the other 90 days is coming up again next week," Ray said. "And as far as I've been led to believe, because he still has not received any inpatient care, he will be held another 90 days."

Ray's son isn't alone.

"Just on probate holds, if I had to give my estimate, we probably have somewhere around 15," Sumter-Lee Detention Center Assistant Director Maj. Chanae Lumpkin estimates about the number of people without criminal charges who are in the county jail, waiting to be transferred to a state mental health facility for evaluation or treatment.

"As much as the Department of Mental Health is trying to work through the numbers, it can be hundreds of people coming from across the state," Disability Rights South Carolina Senior Attorney Anna Maria Conner said. "The problem is that we struggle because we don't have any crisis beds in enough areas of the state."

Conner says while the department deals with a long waitlist of people needing evaluations, it's not uncommon for these people to be held at local jails.

"The local jails end up having to serve the people. They house them. They also have to, obviously, they're housing them so they feed them, but they also have to keep them safe and give them mental health treatment, if they can do so while they're holding them. So it puts a lot of…a big burden on law enforcement, and it's something that…it doesn't matter whether it's the police or the county sheriffs, local law enforcement have been struggling with this to do it in the right way because they're not set up for this," Conner said. "They're not treatment facilities. They're jails first, so it's an inappropriate use of their facilities and of their staff. It's not fair to them. And it's not fair to the actual citizens that go through this process either."

But, Conner says it's where judges send people when it's determined they need mental health support if they fail to make court appearances or go to court-mandated counseling.

According to South Carolina law, "no person who is mentally ill or who has an intellectual disability shall be confined for safekeeping in any jail."

In a statement to News19, a SCDMH spokesperson writes, "While not ideal, the most appropriate and legal placement for someone who has been probate-ordered for mental health treatment, if a hospital bed is not available, is an emergency room, not a jail. While there are wait times for state hospital beds, community hospital beds are available across the state. SCDMH regularly assists community emergency rooms with placements statewide."

Conner agrees that state law prohibits keeping a person without any criminal charges in jail; however, she says there are certain circumstances where probate judges can order this.

"The problem comes in in the fact that the probate judge — those are the judges that actually oversee the commitment process that's in those courts — and those judges again, if they have somebody who doesn't cooperate, they don't show up for a hearing, [the judges] have the authority and the right to issue a bench warrant. And then the person doesn't show up for or somehow doesn't cooperate with the court proceedings, so the next step for the judge is to issue a bench warrant for the rest of that person so that then they can be brought forward," Conner explains. "So the judges aren't doing anything wrong, but because of the overburden of the system, and because we don't have all of the services that we need, particularly crisis beds, and we don't have enough staff, doctors and counselors and so forth who can help with the restoration process, or rather the evaluation process, then you end up with people waiting across the state," Conner explains.

Lumpkin says that process can be lengthy, leaving people waiting in jail cells for months —even years — before they can be properly evaluated. The timeline is "completely dependent on the Department of Mental Health," Lumpkin says.

"Usually we'll have someone that coordinates with the facility whether we're going to do an in person transport. Sometimes they are individuals that their behaviors are just not suitable for transport, so we make arrangements for a video conference instead," Lumpkin explains. "So we don't have just a timetable necessarily. We usually will get an email or a phone call from [a SCDMH] liaison who will say, 'We have this individual, this is your proposed state and the proposed time that we will need them here at our facilities for evaluation."

When it comes to a potential solution to these lengthy wait times, Conner says it's a matter of making sure SCDMH has enough resources.

"You definitely need more staff, you need more doctors and so forth who can actually do the evaluations, you actually need local sites and you need local crisis beds," Conner explains. "Everybody in the state has to realize that we have to commit resources to these individuals because there are a lot of people with mental illness. We have a lot of friends and neighbors, family members, sometimes it's ourselves that have mental illness and it can happen to anybody."

In addition to more staff and more crisis beds, Conner says more legal representation for people struggling with mental health crises is needed.

"You don't always get representation. Or if you do, once the first hearing is held, that person may drop off," Conner says about people in probate court, struggling with mental health issues.

"And so literally, some of those people that are in jails and detention centers are sitting there with no attorneys representing them."

Sumter County Sheriff's Office (SCSO) has requested an investigation into Dinkins' death by South Carolina Law Enforcement Division. Lumpkin says an autopsy will be scheduled soon.