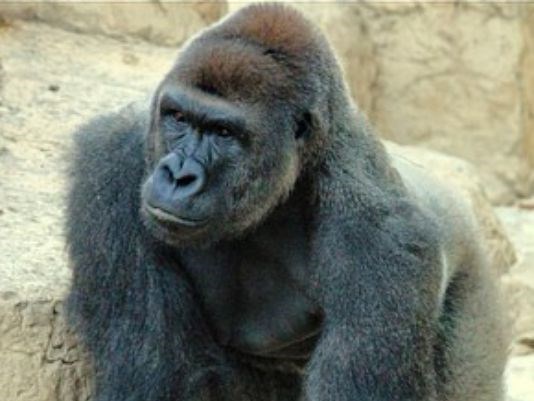

Tongue-in-cheek petitions, Facebook groups and memes seem to have given summer legs to the story about a late 17-year-old gorilla.

Harambe, killed by Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden officials in May after a 3-year-old boy fell into his enclosure, has been memed. So, so memed. That is to say, the internet – from social media to petition sites and beyond to its darker corners – has made him into a running theme that's gone viral.

Teens have tricked Google into naming a street after the gorilla and when matched up with Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton for president, Harambe received 5 percent of the vote in a recent poll.

He even had his name shouted out during the PGA tournament since his death.

On Facebook, the various Justice for Harambe pages have almost 200,000 likes. Justice4Harambe, created the same day as his death, has the most likes at nearly 168,000 as of Wednesday evening.

And one of the more popular tongue-in-cheek petitions was to rename the Cincinnati Bengals to the Cincinnati Harambes, garnering nearly 12,000 signatures. The reason it's tongue-in-cheek? The unprintable hashtag, which originated from comedian Brandon Wardell, according to the meme database site Know Your Meme.

Wardell, with actor Danny Trejo, repeated the unprintable hashtag in a Vine video, which now has nearly 5 million loops.

As The Washington Post and New York Magazine pointed out in their respective profiles of the Harambe meme, the jokes and can be fun have two dimensions:

- A response to the social media outrage and a way to understand it, then to frame it in a new, often comedic, context. As Brian Feldman said in the New York Magazine article, "Memes will flower in the cracks of whatever is circulating on a given social network, and mass outrage, which seizes social media for hours at a time, necessarily provides a fertile ground." For example: the Justice for Harambe petition.

- Even though many of the jokes aren't meant to be offensive, corporate brands and those looking to get connected to the viral name of Harambe aren't going to touch the meme. Again, Feldman, "'Harambe' is still a funny punch line because brands will never touch it." In general, meme culture is hard to penetrate for corporate branding purposes.

The line between sincere memorializing and ironic memorializing gets fuzzier the deeper one dives into the Harambe corner of the internet, however. For example, Justice4Harambe's cover photo is a picture of Harambe with the Paul McCartney quote, "You can judge a man's true character by the way he treats his fellow animals."

There are currently more than 170 petitions on Change.org, including the Bengals one, related to Harambe.

Some, like Justice for Harambe – created a day after his death and which amassed more than half a million signatures – and Make a memorial for Harambe – which has more than 20,000 supporters – seem sincere. Or the petition for safer conditions for animals confined in zoos, which has more than 24,000 signatures.

Others veer more into playfulness, like petitioning Blizzard Entertainment to change the character of Winston in the Overwatch video game to Harambe. Or the petition to put Harambe on the dollar bill, or to change Cincinnati to Harambe City (which actually has more than 1,000 signatures), or to include Harambe in Pokémon Go or to change Gorilla Glue to Harambe Glue.

Then there is the Facebook page for Harambe, the politician, which has nearly 39,000 likes, where the cover photo is the aforementioned unprintable hashtag.

Trolling could be a name for what occurs when the memorializing crosses over into irony.

Whitney Phillips, who literally wrote the book on trolling, "This is Why We Can't Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture," said in The Atlantic that the definition of trolling can be characterized on a scale ranging from harmless to outright harassment, i.e., cyberbullying.

Last month, "Ghostbusters" cast member, Leslie Jones, saw the uglier side of trolling on Twitter, with Harambe used as a racist point of attack.

"As internet culture – and by extension, trolling culture – has become increasingly mainstream, the difference between trolls and good faith aggressors ... has become increasingly difficult to demarcate," Phillips said in the article.

Phillips' theory is that most trolls in the English-speaking web are white, male and somewhat privileged because they enact gender dominance in their trolling.