COLUMBIA, S.C. — A recent report reveals a significant decline in the number of psychiatrists in rural areas, exacerbating the already challenging access to mental health services.

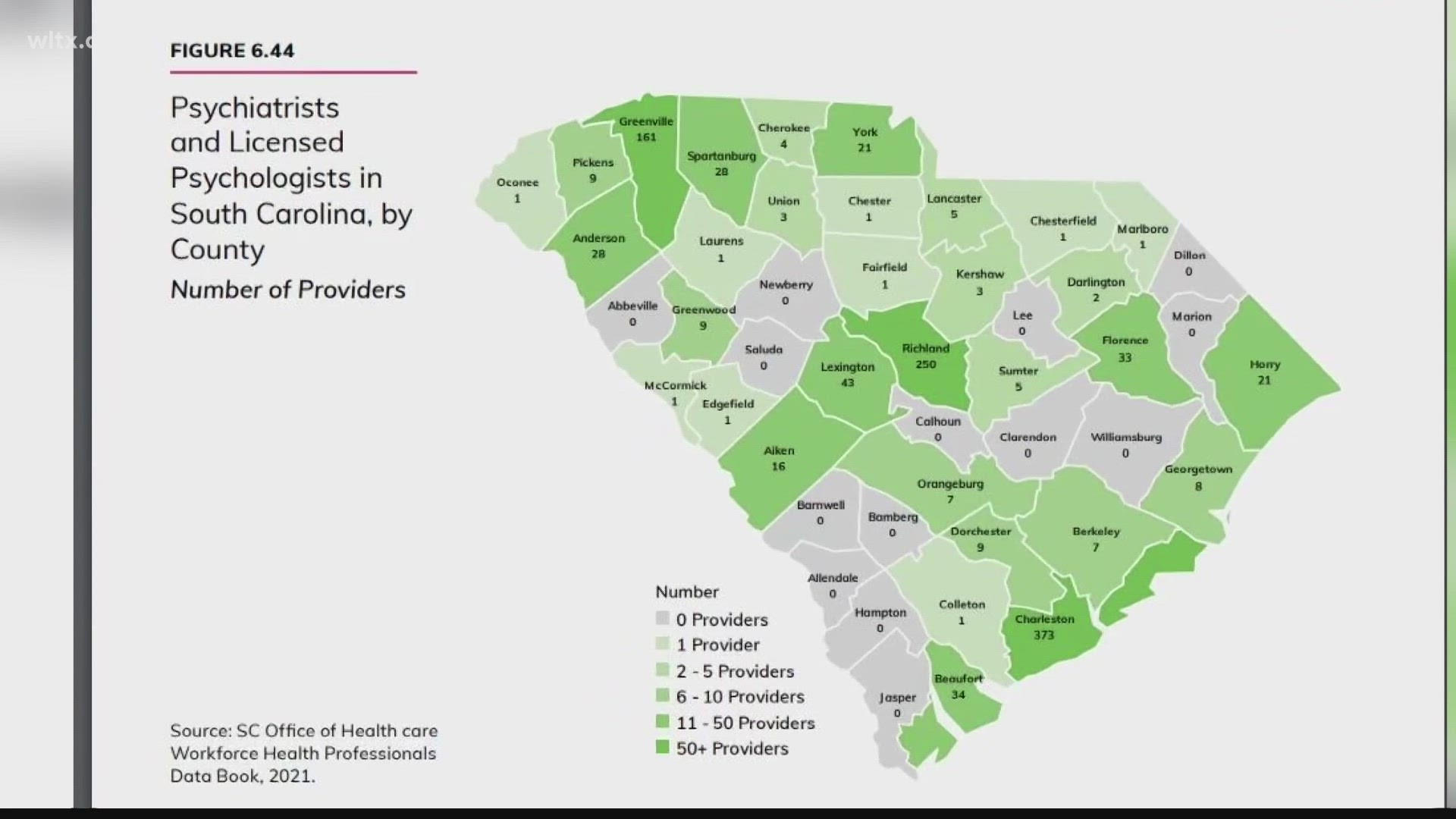

According to the state's annual health report, between 2009 and 2019, the number of psychiatrists in these areas has dropped by one-third. In 14 out of the state's 46 counties, no licensed psychiatrists or psychologists are in private practice. Nine other counties have only one mental health professional.

State programs are working to bridge these gaps. The Department of Mental Health seeks $3.6 million next year for programs to increase access to mental health care.

"It doesn't matter how good your services are; if people can't access them, they're worthless," said Department of Mental Health Deputy Director Debbie Blalock.

About 20% of adults in the country have been diagnosed with a mental illness, making this issue a matter of urgent concern.

Telehealth has emerged as a solution, allowing professionals to conduct online appointments.

"Telehealth is a big help in terms of equalizing care across zip codes," said Blalock. "Now, the challenge is going to be, is there enough broadband."

The Department of Mental Health has deployed various initiatives to address the shortage, including 16 mental health centers with 60 clinics statewide. Additionally, 16 RVs operate daily to bring mental health services directly into communities, successfully reaching people who had not accessed services before.

Despite these efforts, there's a need for additional support. The department is requesting $1 million to enable home visits for people diagnosed with psychotic disorders.

"I think we'll be able to do some really good preventative work with these positions and keep people out of emergency departments because that's not where we want them to go and keep them out of detention centers," said Blalock.

Another $2.6 million would allow the hiring of 32 more mental health professionals to work with troubled youth, offering preventative measures.

"The earlier that people can get into treatment, the better likelihood of them having recovery and going on with a great successful life," said Executive Director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) South Carolina, Bill Lindsey.

"The isolation created by COVID increased some anxiety and depression across all age groups," said Blalock. "But we're definitely seeing an uptick in Children and adolescents."

Implementation of these programs depends on support from state lawmakers.

"It's an equal opportunity illness; so it's one of the few bipartisan issues that are out there," said Lindsey. "I think it's a step in the right direction. Is it enough? No."