Toledo's most prolific serial killer faces parole: Families of victims, prosecutor speak out

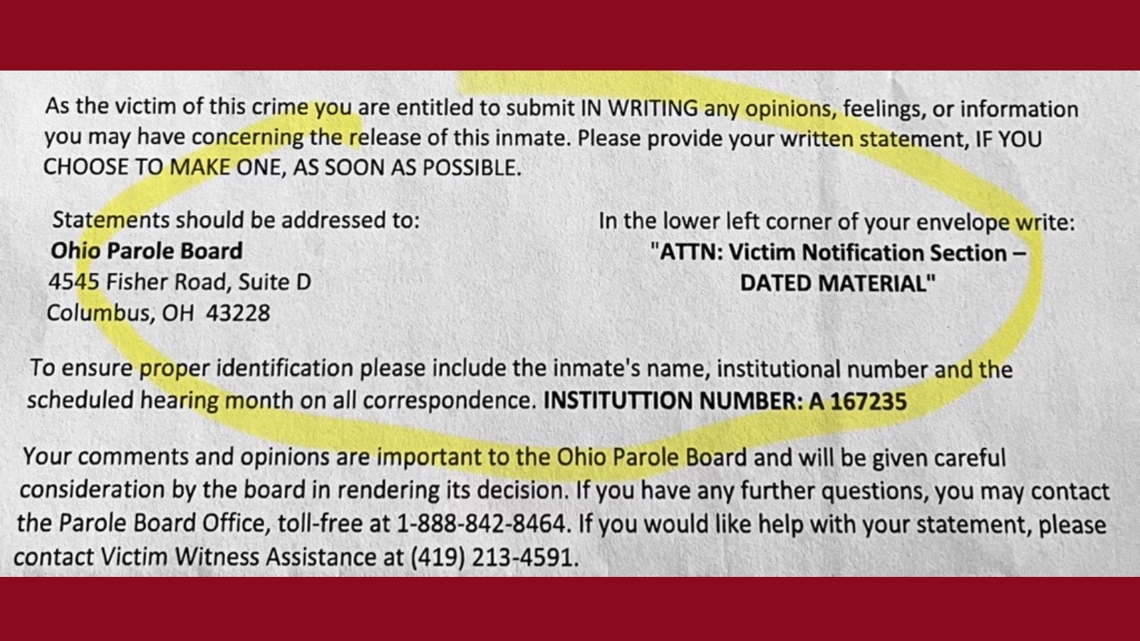

1980's sentencing laws allow a parole hearing for Anthony Cook next week.

Vicki Small. Tommy Gordon. Connie Sue Thompson. Dawn Backes. Denise Siotkowski. Scott Moulton. Stacey Balonek. Darryl Cole. Peter Sawicki.

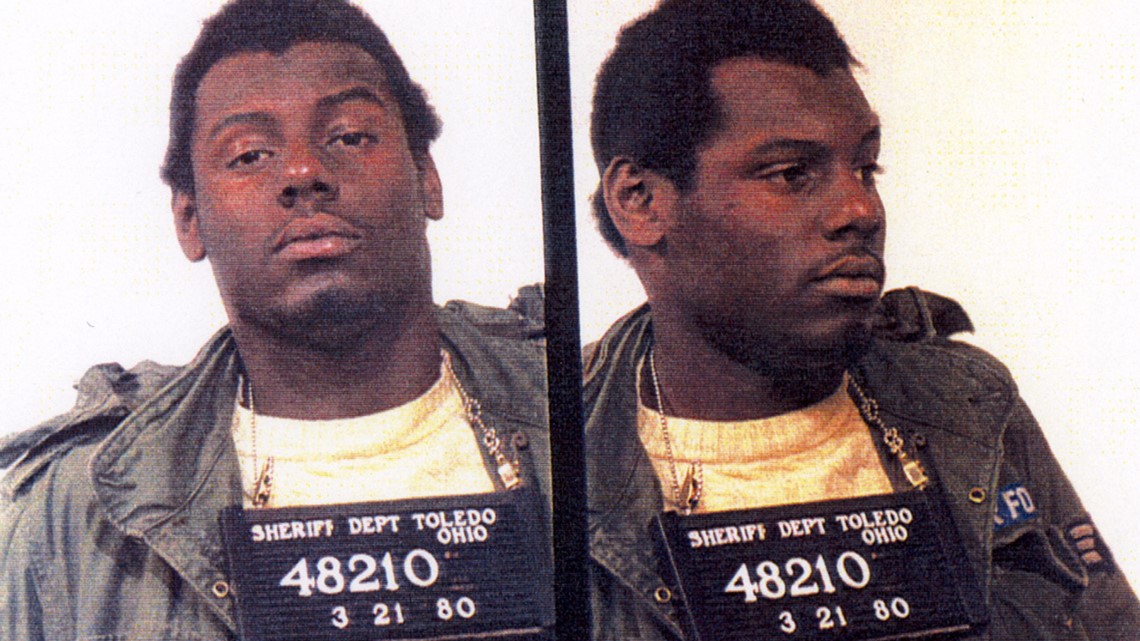

At least nine murder victims between May of 1980 and September of 1981. Anthony Cook is the most prolific serial killer in Toledo history. And on Dec. 5, a parole board will decide if the now-75-year-old should be returned to the streets of Toledo.

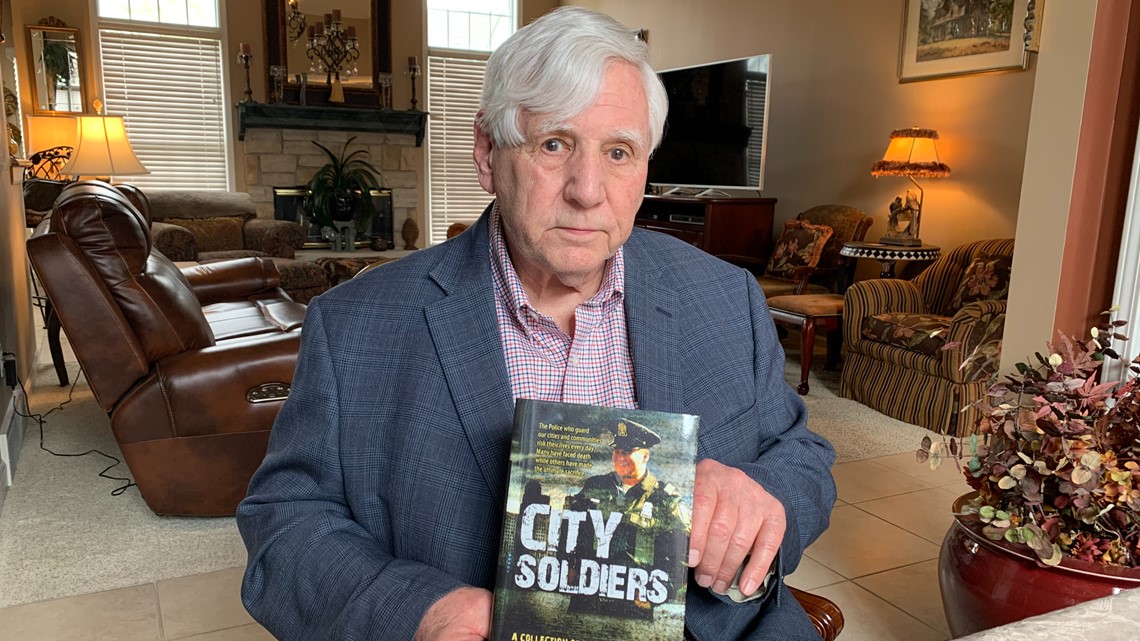

As Cook was stalking young couples, he was being hunted by the Toledo Police Department and Detective Frank Stiles.

“He’s just a cold-blooded killer. If they let him out on parole, it wouldn’t be hardly any time at all before he would kill somebody,” Stiles said. “I don’t have a question in my mind.”

Chapter 1 'Cold-blooded' killers

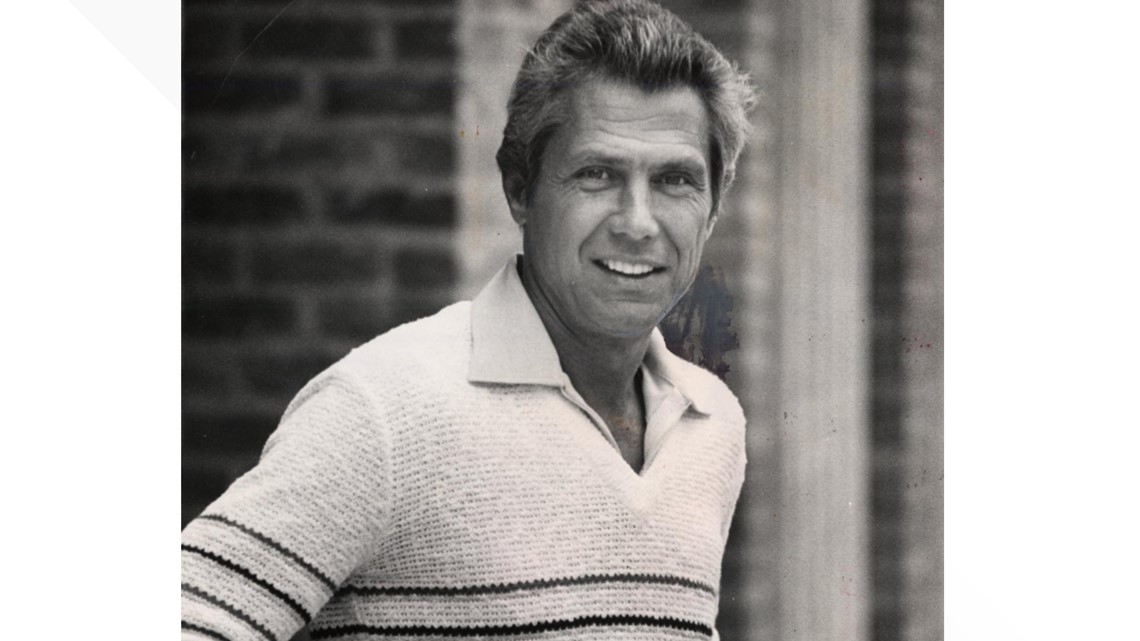

On May 13, 1980, Sandra Podgorski and her boyfriend, Tommy Gordon, were sitting in Gordon’s car in the drive of Podgorski’s Utica Street home. Anthony Cook approached the couple on the driver’s side. On the other side was his younger brother, Nathaniel, who smashed in the passenger-side window with the butt of a rifle.

The men forced their way into the car, drove the couple to a remote area, and after Gordon escaped and began running, Nathaniel shot him multiple times, killing him. Podgorski was raped and stabbed dozens of times by Anthony and left for dead. She did not die, however, and would later be key in convicting both brothers.

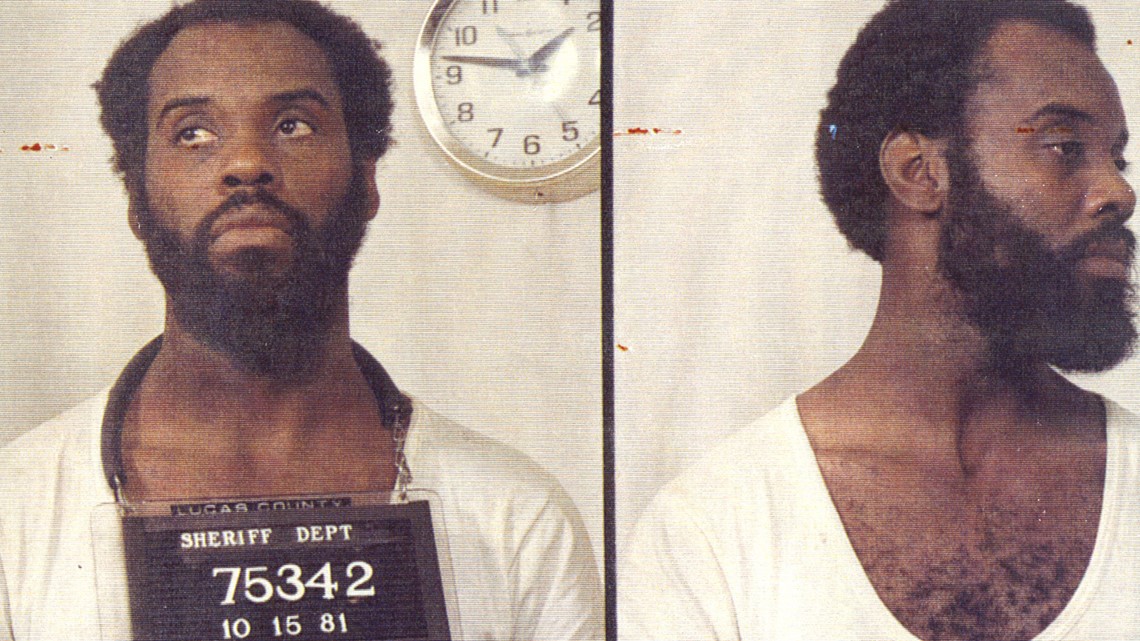

Gordon’s killing was the first of three that the brothers committed together.

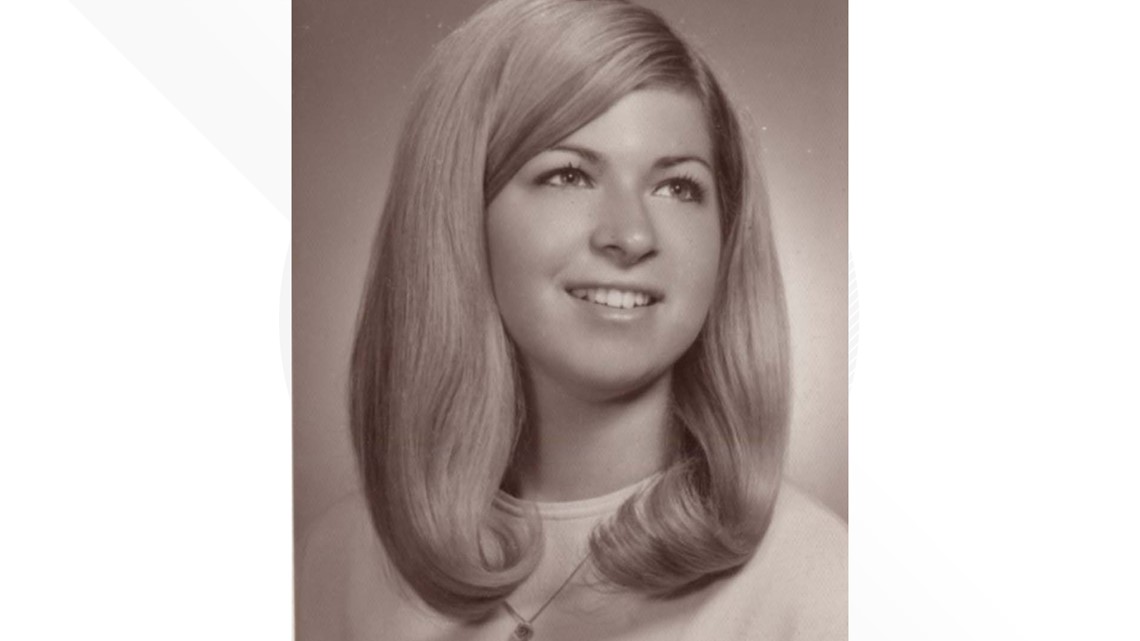

All the murders were brutal, but the Feb. 21, 1981, killing of 12-year-old Dawn Backes seemed to affect Nathaniel to the point that he stopped killing and blended into society without any interaction with police until he was arrested in early 1998.

As she was walking home near the University of Toledo, Dawn was spotted by Anthony, who followed her in his truck, drove to an intersecting street, then jumped out and grabbed her and put her on the floor of the front seat.

He then drove to an apartment to pick up Nathaniel and the men drove her to the abandoned State Theater. Both men raped her in the basement and crushed her with a blunt object.

“It doesn’t get much worse than the little 12-year-old. He picked her up off the street … and to do that to her,” Stiles said, his voice briefly trailing off. “They were cold-blooded, mostly Tony. I handled thousands of cases and I’ve had a lot of murders, brutal murders. I’ve never seen anything like that.”

It’s a pain that has never eased for Dawn’s mother, Sharon.

“She was such a wonderful child. She was good to everybody,” Sharon said. “I always told her that everyone has some good in them. Boy, I sure misled her.”

The killings continued unabated for Anthony, who was fueled by his hatred of white people. Multiple people said it was born when he served time in prison for armed robbery in the 1970s and said white guards mistreated him.

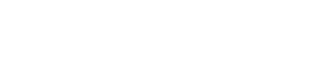

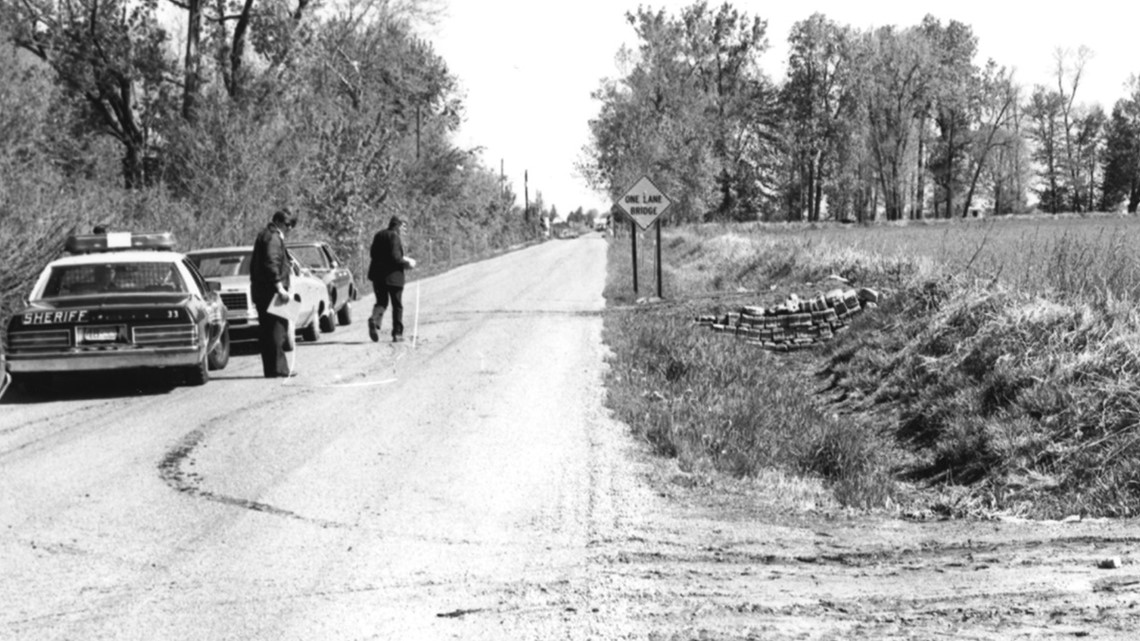

But in September, Anthony’s spree was stopped after attacking Todd Sabo and Leslie Sawicki in their van in the lot of a Toledo apartment building that was in the shadows of the Ottawa Hills police station. Sabo and Sawicki were bound, but Sabo, a nationally ranked wrestler at the University of Toledo, escaped and freed Sawicki, who ran for help, eventually calling her father, Peter.

Arriving before the police, Peter Sawicki began beating Cook, who was able to crawl away, grab a gun and shot both Peter Sawicki and Sabo. Peter Sawicki, a prominent area developer, died, while Sabo survived and struggled with his wounds and emotional trauma for years.

Todd and Leslie testified at Cook’s trial. Shockingly, Cook also took the stand, accusing Sabo of trying to buy drugs from him. In a misstep, he also admitted to owning a gun that was used to kill Peter Sawicki.

Anthony Cook has been in prison ever since.

Chapter 2 A Window in Ohio Law

Ohio’s current death penalty statute went into effect on Oct. 19, 1981. It was a fortunate window of opportunity for Anthony Cook, who killed his final victim – Peter Sawicki - on Sept. 18, 1981.

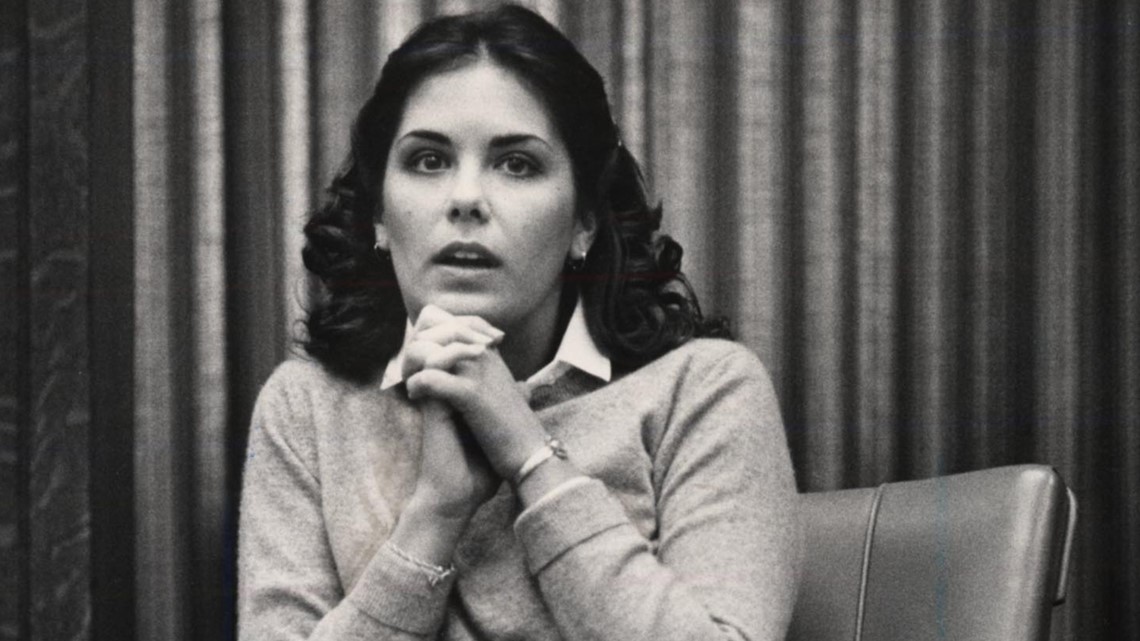

“We didn’t have the death penalty back then, so he didn’t get the death penalty. We didn’t have life without parole then, so he didn’t get life without parole, so he got a sentence that ended with life, but it had a fixed amount of years, and so that allows him to be eligible for parole,” Lucas County Prosecutor Julia Bates said. “It doesn’t mean he’ll get parole.”

When he was arrested a month after Sawicki’s killing, it was clear that Anthony Cook knew he would be eligible for parole. He was alone in an interview room with Stiles.

“He said, ‘Can I ask you a question without being on the record?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t do anything off the record. Anything you say can be used.’ And he said, ‘Well, I can’t ask you then, but it’s a simple question.’ Finally, I said I’d make an exception,” Stiles said. “And he says, ‘What do you think? With all your experience, do you think that a guy who could do this kind of thing would ever be able to get out on parole?’”

Stiles told Cook he believed he would not get out and he still hopes that is the case.

“He is the worst human being I’ve ever seen, talked to, known or investigated. He’s the worst.”

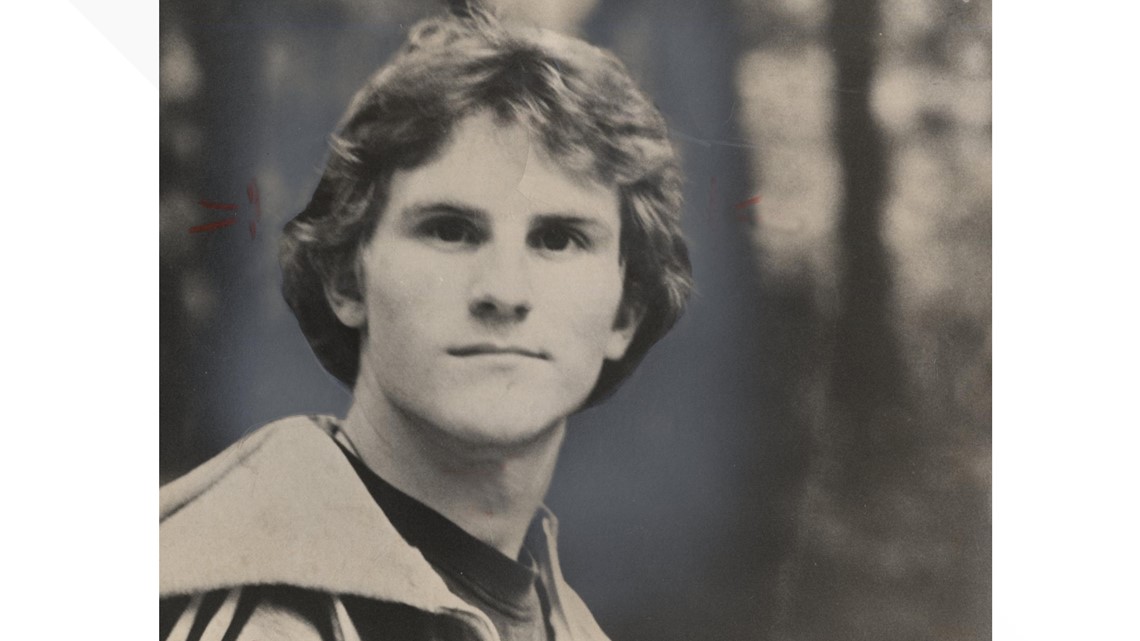

It’s a feeling shared by Steve Moulton, whose brother Scott and friend Denise Siotkowski were killed by Cook after he attacked them in their car as they were parked beside an Oregon apartment building.

“I hope he rots in hell. He’s going to pay for his crimes one way or another,” Moulton said. “If he feels like he’s paid for them now, wait until the next life. I don’t think he’s going to enjoy the rest of it.”

Chapter 3 A Deal, in Exchange for Answers

While at a conference in Cleveland in 1997, Bates was having a drink with then-Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Stephanie Tubbs Jones, who mentioned how DNA was being to determine if Sam Shepard really was guilty of killing his wife, Marilyn, in 1954.

“I went to bed and as trite as it sounds, I woke up at 3 in the morning and I was just wide awake and said, ‘Wow, if they can do this in Cleveland with Sam Shepard, we can do this with the Cooks,’” Bates said. “I knew I had to get home and see if we still had the rape kit.”

The rape kit was from Podgorski’s attack, which was related to Gordon’s murder. The DNA matched not only Anthony Cook but also his brother Nathaniel.

Days before the trial for the Podgorski and Gordon attack, the prosecution agreed to a deal with the brothers. If they would admit their crimes and take a polygraph to verify them, Nathaniel would be released after 20 years.

Bates was going to try the case alongside then-assistant prosecutor Dean Mandros, who is now a Lucas County Common Pleas Court judge.

“He was very seasoned, compassionate and just an excellent trial lawyer. We sat together on Saturday morning, before the trial was to start on Monday. We said, what are we going to do? We’re talking about 20-year-old DNA at this point. That was no sure thing, and also a woman who had been through a terrible crime.”

Nathaniel Cook’s sentence began in 1998 and with nothing the state could do, he walked free in 2018 and lives on West Central, in the shadow of the Old West End Academy.

“You think that 20 years is a really long time, that he’s going away and we’ll never have to think about him again. Then all of a sudden, 20 years is up and he’s coming home,” Bates said.

She keeps multiple pictures in her office of court proceedings related to the Cooks.

“We keep the pictures on the wall in the office so that we remember and that we never forget.”

Chapter 4 Chilling Confessions

In April of 2000, the Cooks lived up to their terms of the agreement. Nathaniel and Anthony detailed all of the crimes that they said they committed.

11 Investigates has seen the interviews. It is striking how calmly and matter-of-factly Anthony describes the murders, even describing his first murder. Vicki Small was abducted, raped and killed by him on Dec. 20, 1973.

“He would talk just like you and I are talking. He was very cool, collected, and calm. He showed no emotion,” Stiles said. “He’s a psychopathic killer. He didn’t have any feeling about the killing. He enjoyed it. Tony Cook enjoys killing.”

He showed little emotion, but he did find humor in two of his killings. In one case, he chuckled that he approached the passenger side of a car and a victim refused to lower the window. He told the detectives he thought it was funny that the man thought the window would protect him.

When he discussed a separate case, he found it amusing that the female victim was more concerned about something happening to her father’s car than her own safety, even though he was planning to kill her.

For the most part, his brother corroborated many details of the crimes he was involved in, though there were slight differences.

But Anthony truly seemed to enjoy the recounting, even explaining how he would change up weapons so as not to establish an MO the police could track.

“The guy’s whole history of life is brutality, especially against whites,” Stiles said. “If anybody could possibly let this guy out of prison and feel comfortable with themselves, they’ve got a strong constitution that I would never think someone could have.”

Chapter 5 Bond Through Tragedy

More than 40 years later, there is still a bond to those involved with the Cooks’ murderous rampage. Six years ago, they comforted each other when Nathaniel walked free. Every 10 years, the scab is pulled off and they come together to fight to keep Anthony from joining his brother.

But this time, it feels different to Moulton.

“Everything that we learned up to that day was that Anthony Cook is in jail for the rest of his life … period. These parole hearings are going to come up because it’s his right. What we learned is that it’s not 100% accurate that he’ll never get out.”

He said he was told that this time Cook has to be given a serious hearing.

On Jan. 27, 1981, Cheryl Bartlett was attacked by both Cooks as she was walking home with her boyfriend, Bud. As she hugged Bud, a bullet was fired into her back. It has led to a lifetime of physical misery for Cheryl and one surgery after another.

When asked, she provided a message to the parole board:

“I have been dealing with the Cook brothers and what they did to me for more than 40 years. I’m 62 now,” Cheryl said. “If he gets out, he’ll do it all over again. All he knows is prison life. He doesn’t know what it’s like to be a human being.”

Bates has been dealing with the Cooks most of her professional life. She knows of the fear caused by them in the community and the devastation caused to so many families.

She was asked her message to the community and if she believes Anthony could be released.

“My message is: Let’s hope not. I don’t think so,” Bates said. “I’ve been doing this job for 48 years. I’ve not seen too many who are worse than Anthony Cook, and those other people are still locked up. I think he will be as well. I’m fairly confident that that’s what will happen.”