ROSWELL, Ga. — Three short paragraphs appeared to tell the whole story.

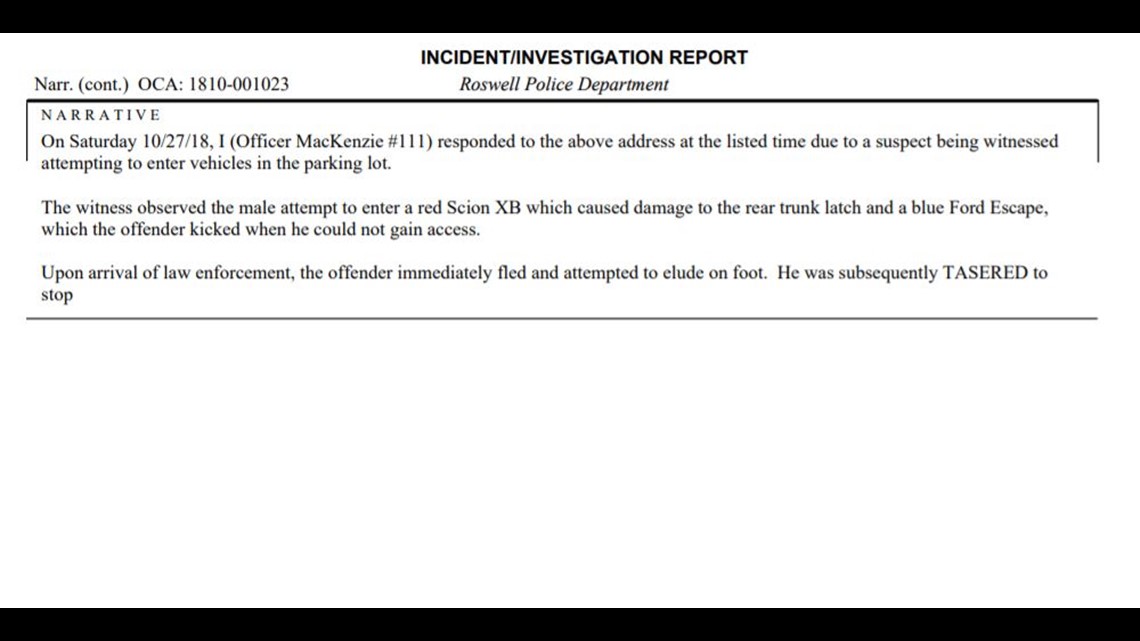

Roswell Police Officer Daniel MacKenzie wrote in his October 27, 2018 report that a man was trying to open car doors in an apartment parking lot, and that he ran when police showed up. Officer Mackenzie’s last sentence said, “he was subsequently tasered to stop,” with no period at the end.

There was no period because the "confidential" officer narrative goes on for six more pages.

Hidden from the public, the full police report described Officer MacKenzie tasing and punching the handcuffed suspect in the backseat of his patrol car.

11Alive's investigative team, The Reveal, was alerted by a source within the Roswell Police Department to file an Open Records Act request immediately after the arrest in 2018. The incident report we received in response was six pages long, with that three-paragraph narrative on page four.

A few standard redactions blacked-out dates of birth and cell phone numbers, but there was no sign of anything missing. The report even had the pages sequentially numbered one through six.

The Reveal obtained a copy of the full report that Officer MacKenzie filed with the case. It is twice as long as the public copy the police department gave us — 12 pages instead of just six. The real report is also sequentially numbered on pages one through 12.

The full report detailed the tasing and punching of the handcuffed man in the backseat of the patrol car. It also explained that MacKenzie had just returned from his friend’s funeral days earlier.

“There should not be entire paragraphs or pages of information missing from one report to another," said Hans Appen, publisher of the Roswell Herald and four other North Fulton newspapers. “You expect redactions, you expect cell phone numbers, you know, maybe dates of birth for minor children, those types of things to be missing from a report, not entire paragraphs or pages of information,” Appen added.

Appen Media Group sued Roswell Police in 2018 for routinely withholding and delaying police incident reports from its newspaper reporters.

The Georgia Open Records Act requires police departments to release initial incident reports to anyone who requests them. Unlike evidence and other investigative records, the police report is always public and subject to release regardless of the status of the case.

Roswell denied any wrongdoing in the suit, but the city settled with Appen, agreeing to pay half of his attorney’s fees, and promising to release police records to his reporters without delay going forward.

The suit cost Appen $20,000. Half of that was paid by Roswell taxpayers, and the rest was covered by citizens who donated to Appen’s GoFundMe page set up to fund his lawsuit against the city.

“The citizens of Roswell really came through for us,” Appen said.

Chief James Conroy, hired after the previous police chief resigned amid our series of investigations into Roswell Police misconduct, said he’s “implemented training for all officers to insure that police incident reports are properly completed so the narrative is included with the initial report.”

Two sets of books. Not a bug. It’s a feature

Several police departments throughout Metro Atlanta also conceal full officer narratives from incident reports released to the public and the press.

In our two-year investigation, The Reveal examined incident reports from dozens of police departments. While the practice of excluding full officer narratives is widespread among departments using different systems, we did find narratives missing more frequently from agencies using specific software.

OSSI, an incident reporting system popular with many police departments in Georgia, labels the officer narrative with a banner: “the information below is confidential - for use by authorized personnel only.”

Georgia law allows for no such exception to the Open Records Act. If an officer’s narrative is part of the initial incident report, it must be released to anyone who asks for it. In any case, agencies are required to tell requestors that information was redacted or withheld from a public record, and they must cite the relevant code section that authorizes such redactions.

Another feature of the software, according to a source within the Roswell Police Department, is that it allows officers and records clerks to create different versions of an incident report, depending on who is receiving it.

If the report is for the press or the public, the resulting PDF or printout will completely omit the officer narrative, except for a brief abstract on a previous page. If the report is for the case file or the courts, the full narrative is included.

We tried to reach OSSI for comment, but the parent company was recently sold and it's not clear who runs the company now.

The Reveal found police departments using a similar method with other incident reporting software.

We asked Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr for an interview on the subject, offering him an opportunity to address the widespread practice by police departments of omitting entire pages from police reports without telling requestors they’re missing. A spokesperson replied that the attorney general and his office “is unavailable for an interview.”

Police misconduct hiding in missing pages

Officer Daniel MacKenzie remains under criminal investigation for punching and tasing the handcuffed suspect in 2018. He resigned from Roswell Police during an internal investigation in 2019, and Georgia Peace Officer Standards and Training revoked MacKenzie’s police certifications.

Police misconduct cases often languish for years in the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office. MacKenzie’s case sat untouched for 22 months after the DA dropped all charges against the man he arrested.

Back in 2018, 11Alive Chief Investigator Brendan Keefe had contacted the public defender representing the suspect. Keefe told the defense attorney that one of the reasons the officer hadn’t shown up in court may have been the fact that he was under investigation for punching her client.

After learning of the internal investigation from The Reveal, the public defender asked to see the police video of the incident. When the DA’s office reviewed the video, prosecutors immediately dropped the charges against the defendant and opened an investigation into the officer.

As a result, the video remained secret for another two years.

Police videos, unlike incident reports, are considered evidence exempt from release under the Open Records Act. Police departments are not required to release video to the press or the public so long as a case remains open.

The same goes for cases where police officers are also the targets of a criminal investigation.

Combined with the information hidden in the ‘confidential’ narrative written by Officer MacKenzie, the public had no idea a Roswell Police officer had punched and tased a handcuffed suspect until we published this story.

‘Starting to look like a cover-up’

The Reveal requested and received the skinny incident report just days after Officer MacKenzie punched and tased the handcuffed suspect in the backseat of his patrol car.

We would have to wait two full years for Roswell to give us the video and internal affairs report.

Once the Fulton County District Attorney dismissed the charges against MacKenzie’s suspect and started investigating the former officer instead, we asked the DA’s office to release the video.

Month after month, we kept emailing the DA’s office about the status of the case. When we asked “what is taking so long?” in July 2019, the DA’s spokesperson replied “the office is conducting a thorough investigation.”

In reality, the Trial Division of the DA’s office sat on the case until late 2020, when it was finally sent to the Public Integrity Division, according to Paul Howard.

After two years of regular requests and delays, we asked Howard’s office for the video again in October of 2020. 11Alive Chief Investigator Brendan Keefe wrote, “at this point is it starting to look like a cover-up.”

Then-District Attorney Paul Howard replied that he was taking the case to the grand jury. He ordered Roswell Police to release the video to 11Alive.

Howard’s successor was elected the next month.

District Attorney Fani Willis is currently revamping her office’s Public Integrity Division, renaming it the Anti-Corruption Division. As part of the overhaul, Willis promises to clear the case backlog and speed up police investigations that took years under her predecessor.

Willis’ spokesperson told The Reveal that all pending investigations she inherited are subject to review, including the case involving now-former-officer MacKenzie.

‘Somebody needs to get some…revenge’

Police videos show Officer Daniel MacKenzie opening up the patrol car door and issuing contradictory commands to the handcuffed suspect in the backseat.

“Come here! Come here! Stop! Stop! Come here,” MacKenzie can be heard alternately ordering the suspect who had his legs wedged around some traffic cones stacked in the patrol car footwell.

MacKenzie had already tased the suspect through the open patrol car window, which was protected with metal bars.

The officer grabbed the suspect and punched him on the right side of the man’s head.

An internal investigation showed that the interior door handles were disabled, and there was no way for the suspect to get out of the car. The bars on the windows and divider between the front and back seat similarly prevented any chance of escape.

Officer MacKenzie decided to forcibly remove the man from the secure backseat to the roadway, even as the sirens of police back-up units could be heard approaching.

“Was there anything that was influencing your behavior on this day when you were transporting [the suspect]?” the internal affairs sergeant asked.

“With everything going on, I have PTSD,” MacKenzie responded. “I don’t like to use the word trigger, but I was overwhelmed with the Gwinnett County incident, the murder of Officer Toney on that suspicious call,” he added.

Gwinnett County Police Officer Antwan Toney had been gunned down in 2018. MacKenzie worked at the same police department and had helped train Officer Toney.

Officer Toney’s funeral was just days before the incident that would end MacKenzie’s career.

MacKenzie’s lieutenant was also interviewed by internal affairs.

“Somebody had said that Officer MacKenzie had made a comment — alleged comment — about the individual who had killed the Gwinnett County police officer,” Lt. Smith said he had heard. “Somebody needs to get some ‘get back’ or revenge or something in that manner.”

The Reveal reached out to Daniel MacKenzie for this story. He did not respond.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.