ORANGEBURG, S.C. — During the time of segregation, many businesses across the nation wouldn't accommodate people of color.

Even though they had money, African Americans weren't allowed to do business in certain places because of the color of their skin.

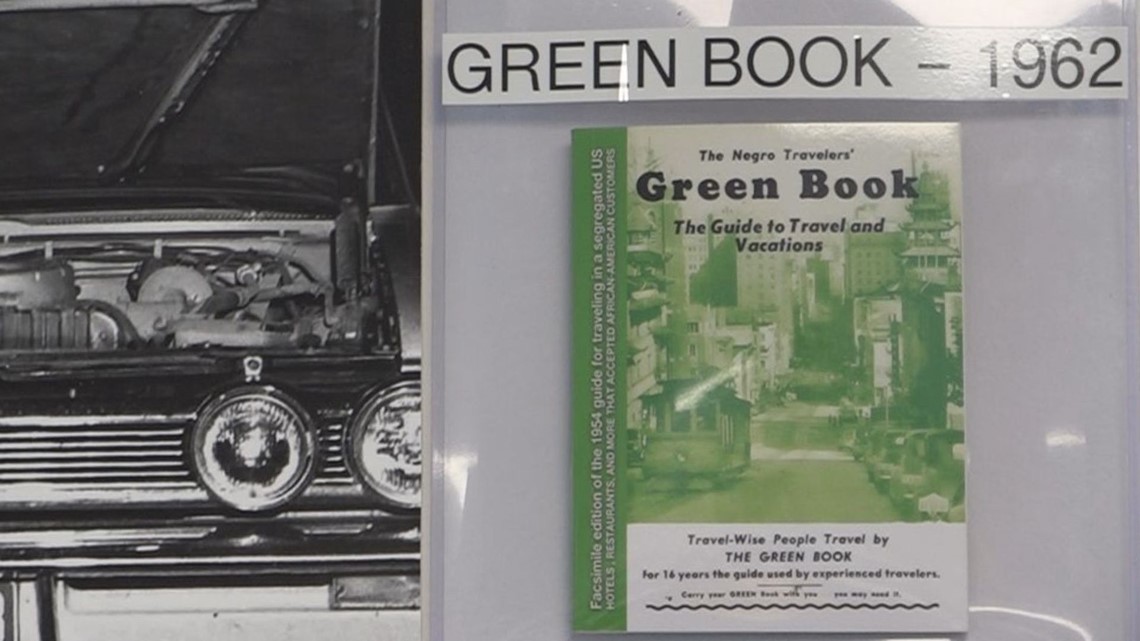

For that reason, the Negro Travelers' Green Book was created.

It listed businesses like hotels, restaurants, barbershops, and much more in different states that would welcome people of color.

“In almost every home, the Green Book was a standard. Maybe not quite as popular as the Bible, but still very useful during those days," said Cecil Williams, Orangeburg Native and Creator of the Cecil Williams South Carolina Civil Rights Museum.

Cities around South Carolina are included in the Green Book. In this story, News 19 explores the Orangeburg connection.

"I remember one occasion when my own family benefited very greatly from the Green Book," said Williams.

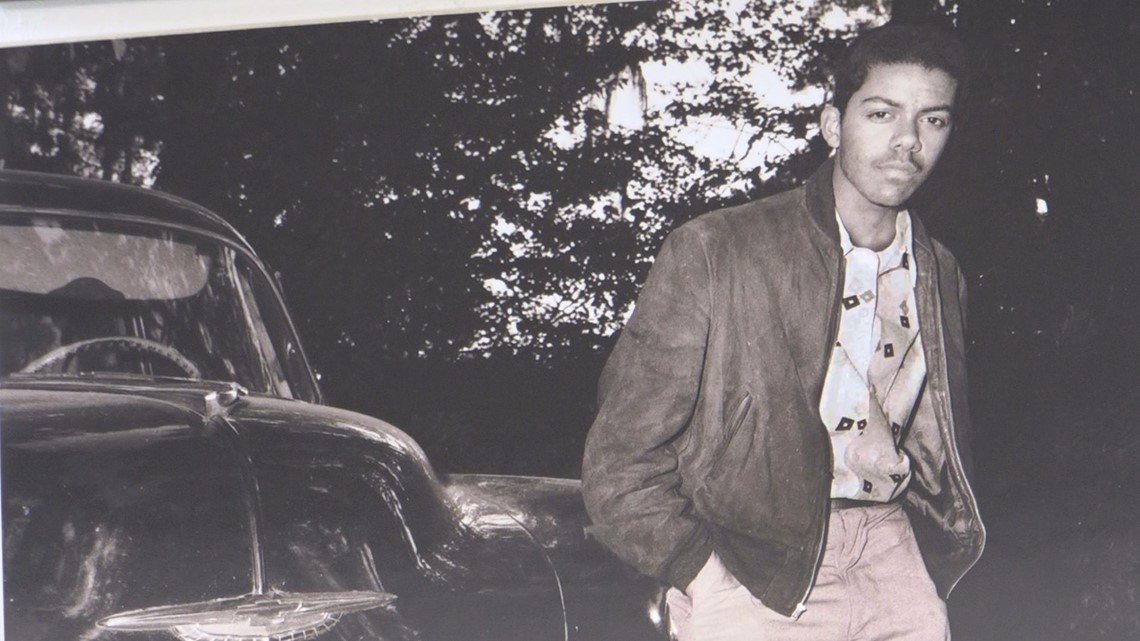

Williams, 83, recalls taking a road trip with his family when he was 25.

The year was 1962, and they were traveling from Orangeburg to New York City.

"The further north we got, the less rigid segregation patterns and things would open up," said Williams.

As the family drove on Highway 301 near Fayetteville, North Carolina, their car broke down. The repair would keep them there for the night.

To find a place to stay, they looked through the Green Book.

"There were so many places where you were discriminated against and you could not go, signs of racism, white only," said Williams. "Had it not been for the green book, we would not have been able to find a place to stay overnight."

As a professional photographer, Williams took a snapshot of the moment their car broke down.

The photograph is on display at the Cecil Williams South Carolina Civil Rights Museum in Orangeburg.

"I have a picture of the hood of the car and my mother and my sister are standing by," explained Williams. "We are waiting for the wrecker to come and haul our car away."

The Green Book played a critical role in keeping the Williams Family safe that day.

The book's pages listed hundreds of businesses from coast to coast where African Americans were welcomed.

The City of Orangeburg lists one location: Johnson's Tourist Home at 1220 Lancaster Street.

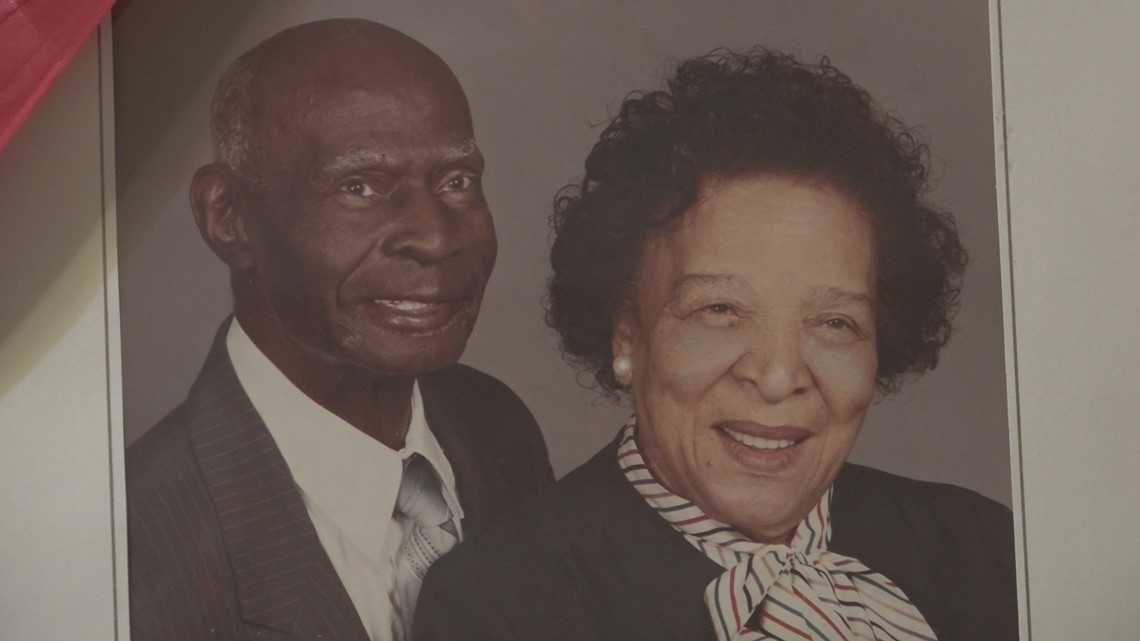

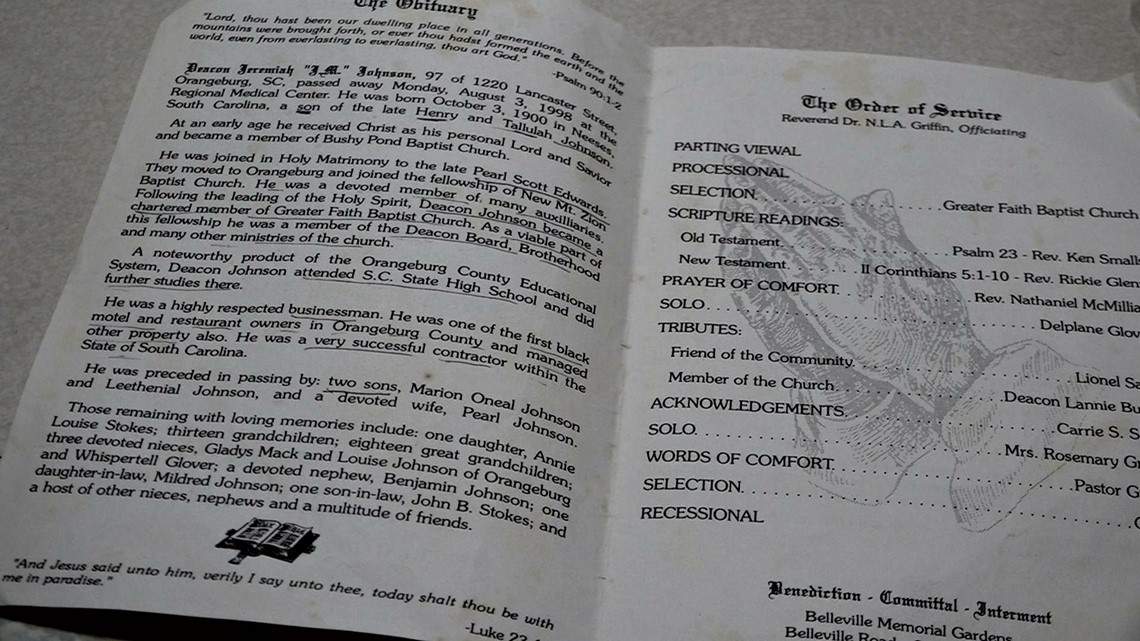

Louise Johnson, 92, says her Uncle Jerry Johnson and his wife Pearl owned and operated that home.

"He was my father's brother," said Johnson.

Jerry Johnson lived at 1220 Lancaster. His home also had rooms for rent at a good price.

Mrs. Johnson says her uncle's doors were always open, and her aunt would always have something to serve.

"He had an apartment house and he had a business, a restaurant," Johnson recalled. "His wife was a cook. She love to cook and sing, she was a sweetheart."

Family members say the location is in close proximity to South Carolina State University and Claflin University. They believe it's possible that many of their uncle's guests included students and educators.

Mrs. Johnson remembers her uncle as one of the first black motel and restaurant owners in Orangeburg County. His obituary states he was a successful contractor in South Carolina.

"He was just a person who loved to give and help people."

In 1975, Jerry Johnson donated the property to his place of worship where he also served as a deacon: Greater Faith Baptist Church.

It stands on the property today, along with a Child Development Center on the very spot where Johnson lived.

"The Calling on uncle Jerry's life was very sure and it helped a lot of people," said Glenda Middleton, daughter of Louise Johnson.

The family's goal is to preserve their uncle's legacy, perhaps with a historical marker outside the church.

"To relay [the story] to those who walk through that area. There are many who come and go," said Middleton. "Greater Faith has a soup kitchen and there are many folk who aren't members of our church and are members of the community...for them to know the hollow grounds that they walk on."

Family members believe a marker would help recognize their uncle's hard work while also educating the community about the rich history of Orangeburg featured in the Green Book.

"They will think things went on other places and locations, but not right here where they live," said Delphine Glover, daughter of Louise Johnson. "They need to know that they to have a rich history right in their own town...That is a part of Black history."

Williams adds that other businesses in Orangeburg, although not in the Green Book, would still welcome people of color. An example, he says, is what used to be known as the Pinckeney House off Highway 601 leading into Orangeburg. The Pinckeney House, Williams recalls, used to be a restaurant and motel. The building was eventually torn down.

Now, the property off Magnolia and Jamison Streets is empty.

For those interested in checking out the Cecil Williams South Carolina Civil Rights Museum, they are closed for in-person visitors, but you can still learn about the history inside with a free virtual tour.

This story is based on the Spring 1956 Edition of the Green Book, available in the University of South Carolina University Libraries Digital Collection.