![635544145262935942-stinney [ID=20535109]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/33d97f8a03d5ea06baca0f7a30eca34c8bd87643/r=500x281/local/-/media/2014/12/17/WLTX/WLTX/635544145262935942-stinney.jpg)

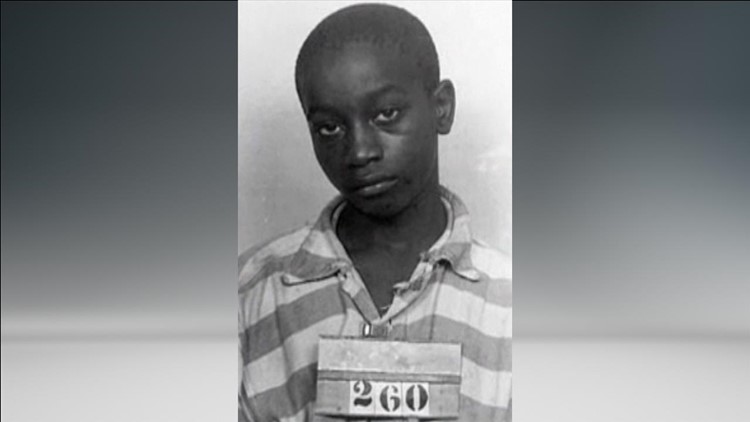

Sumter, SC (WLTX) - A judge has thrown out the conviction of a 14-year-old South Carolina teen who was convicted of killing an two girls 70 years ago.

Judge Carmen Mullen issued her ruling Wednesday in the case of George Stinney Jr., saying she found "fundamental, Constitutional violations of due process" in the 1944 prosecution of the teen.

"I just wish my mama and daddy were here to see this day," said Amie Ruffner, Stinney's sister. "It was a wrongful killing. He was too young...they didn't give him a chance."

Mullen make it clear that in rejecting the original verdict, she was not making a judgment on the guilt or innocence of Stinney.

In 1944, Stinney was convicted of killing 11-year-old Betty Binnicker and 7-year-old Mary Emma Thames in the Clarendon County town of Alcolu. Three months after his trial, he was executed in the electric chair.

The girls were white, and Stinney was black. All all-white jury heard the case, and rendered a verdict after 10 minutes of deliberation.

For years, his family and civil rights supporters questioned if the original trial was fair. Stinney's advocates said the young man was forced to confess, didn't have proper counsel, and wasn't allowed to have his parents around when he was questioned. Many of the records in the case, including the confession, have been lost.

"I was born in Alcolu," said historian George Frierson, who researched the case for years before bringing that research to attorney's. "The stigma of having my birth place attached to a travesty like this, it's kind of hard to swallow."

In January, lawyers for the Stinney family argued in court that the verdict needed to be dismissed because of errors in the prosecution. But relatives of the victims, along with Third Circuit Solictor Chip Finney, argued the previous ruling was fair and should stand.

"It's a legal Hail Mary, and it was caught in the end zone," said Miller Shealy, a professor at the Charleston School of Law.

Shealy argued in court that an old legal argument known as a writ of coram nobis, which Shealy said goes back some 600 years, supported their arguments.

Mullen said records from that era were poor and scant, including a lack of any transcript, making it difficult to sort through some of the key details in the case.

However, Mullen in particular felt that the confession in the case was compromised. During the trial, psychologist Dr. Amanda Salas, a defense witness, said Stinney likely confessed because of the power differential between his position as a 14-year-old black male being questioned by white, uniformed law enforcement in a small segregated town.

""Methods employed by law enforcement in their questioning of the Defendant may have been unduly suggestive, unrestrained, and noncompliant with the standards of criminal procedure as required by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments," Mullen wrote. "We know that law enforcement separated the Defendant from his parents and otherwise took advantage of his age and stature to garner a result they determined to be true and just."

Mullen wrote that Stinney didn't get adequate representation, saying his attorney did little to defend him and asked few cross-examination questions. She also said there was never an effort made to move the location of the trial, despite the fact that likely much of the town was angry over the deaths, and that the jury was likely not impartial.

She also concluded that the sentencing of Stinney to death at the age of 14 amounted to cruel and unusual punishment.

"Given the particularized circumstances of Stinney's case, I find by a preponderance of the evidence standard, that a violation of the Defendant's procedural due process tainted his prosecution," she wrote.

One of Stinney's sisters, Aime Ruffer, who said she was with her brother when the two girls approached the two and asked for 'maypops,' a type of flower, spoke to News19 over the phone from her home in New Jersey.

Ruffner said she has always believed in her brother's innocence.

A relative of Binnicker's, Carolyn Geddings, said she she believes Stinney committed the crime, while also admitting that Stinney was not given a fair trial.

Shealy said Finney's office could appeal the ruling.