He ripped anyone and everyone. He refused to call players by their actual names. If you were in his circle of trust, you were given a nickname. Otherwise, you were just a number to him.

He was a football original, among the last of the dinosaurs.

Ryan died Tuesday at age 85 after cutting a large swath across the NFL. He was a linebackers coach for the Super Bowl champion Jets in 1968, helping Joe Namath make good on his guarantee. He was the mastermind behind the "46" defense in Chicago, a scheme built solely on the premise of traumatizing quarterbacks.

![Former NFL coach, defensive mastermind Buddy Ryan dies at 85 [oembed : 86496930] [oembed : 86496930] [oembed : 86496930] [oembed : 86496930] [oembed : 86496930] [oembed : 86496930]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

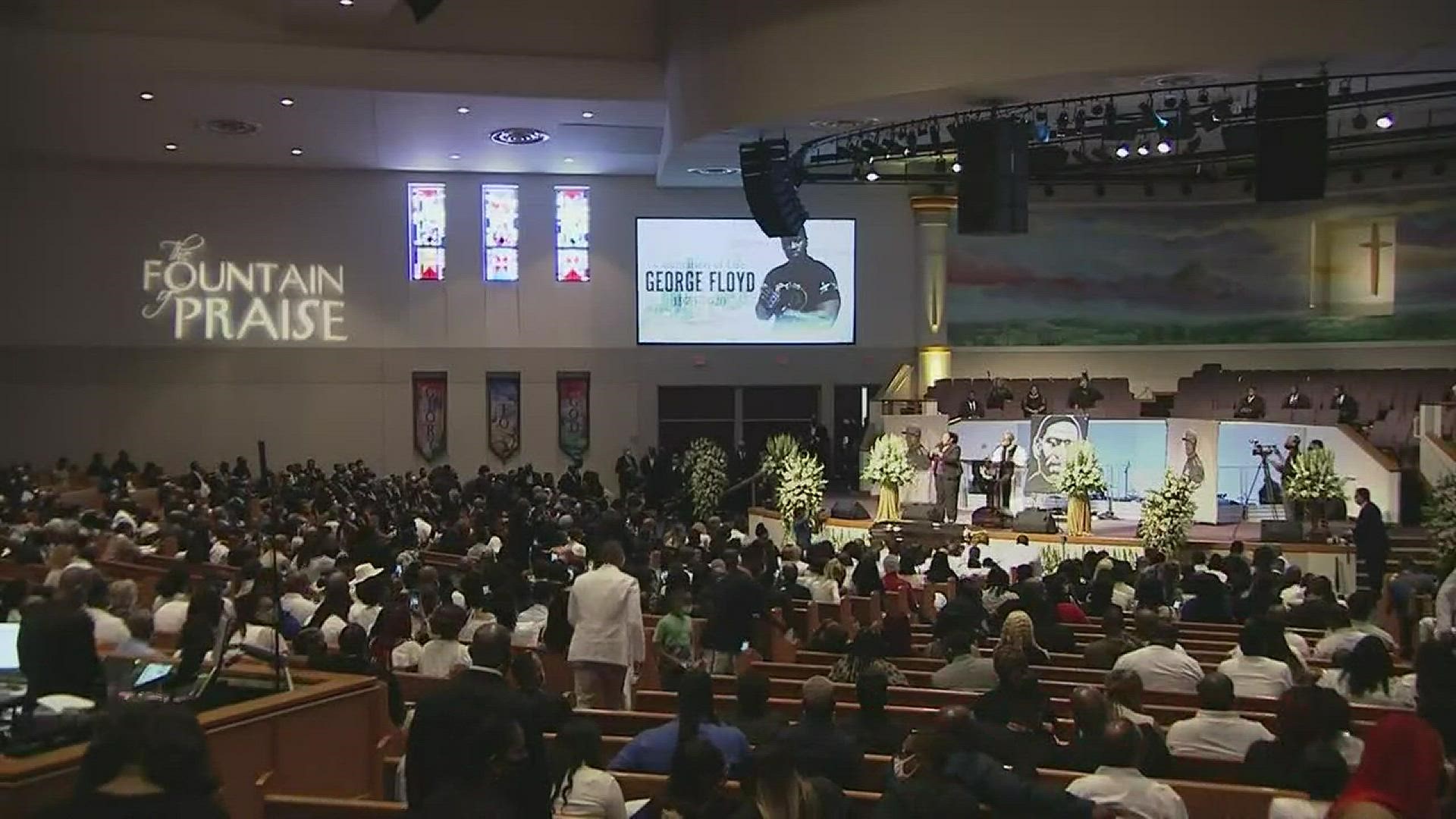

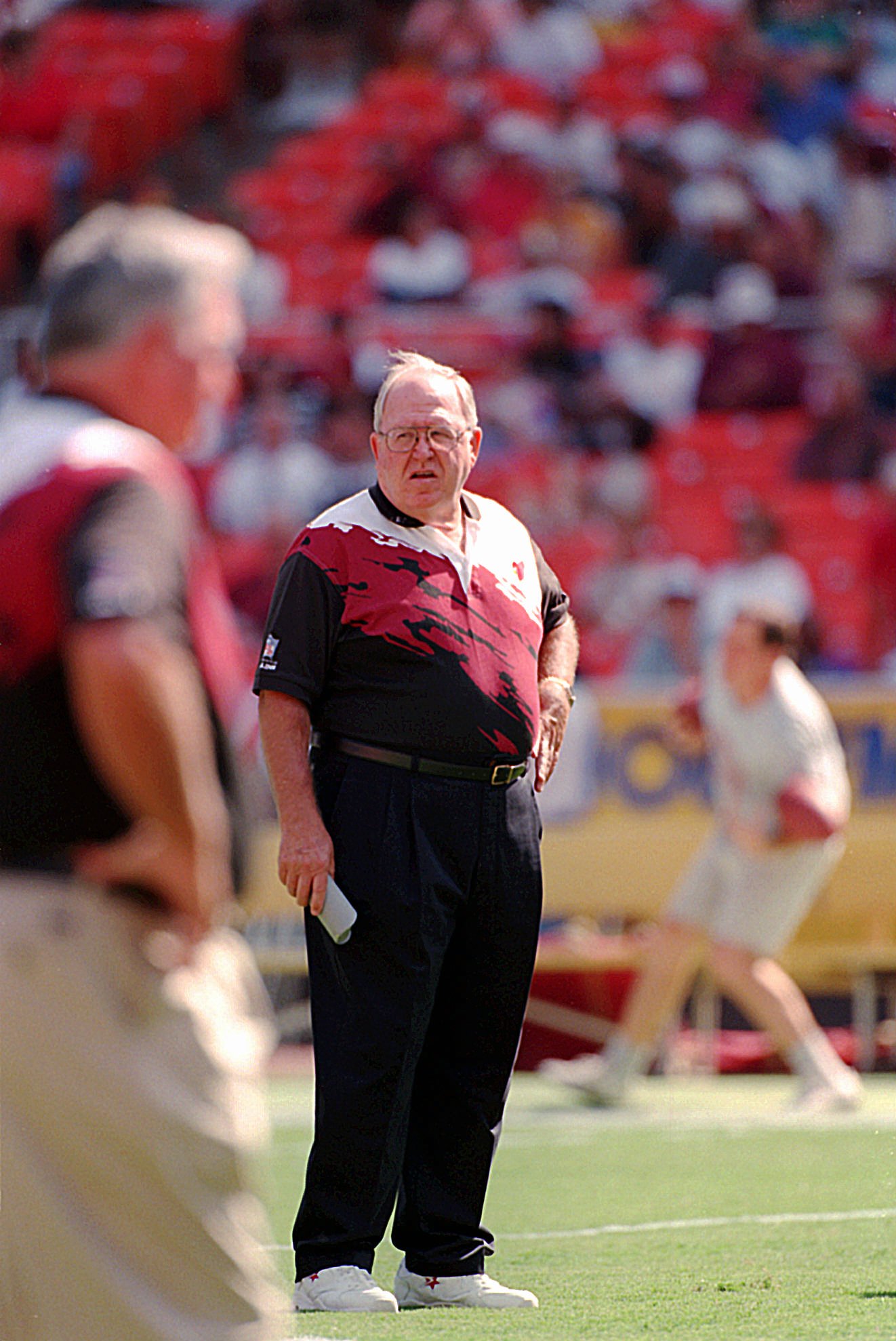

He came to Phoenix in 1994 and uttered one of the more famous phrases in the city’s sporting history:

“You’ve got a winner in town.”

In retrospect, the claim was more pathetic than prophetic. But at the time, the hiring of Ryan did something very important in the Valley. He brought excitement, energy and the eyes of the nation to a franchise that had spent the first six years in Arizona squandering its fan base.

He was the football team’s answer to Charles Barkley, who came to Phoenix a year earlier and promptly led the Suns to the NBA Finals.

“I’ve talked to players here that didn’t like Buddy, that felt he was past his prime,” said former NFL safety Doug Plank, a Ryan disciple in Chicago. “When he came to Arizona, he was at the end of his career. I don’t know if he had the same focus or efficiency that he had earlier in his life. And I know he looked really silly for some of the things he said or did.

![Buddy Ryan was just as fiery as a high school football head coach in Texas [oembed : 86497102] [oembed : 86497102] [oembed : 86497102] [oembed : 86497102]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

“But you can’t argue when you grab the playbook of our ‘46’ defense. It was so innovative, and one of a kind. He wasn’t afraid. He would try anything. He was the Wright Brothers, seeing if it would fly or not.”

In some ways, Ryan was very similar to current Cardinals head coach Bruce Arians, as both men found coaching fame much later in life. Arians was 60 when he earned his first shot as NFL head coach, while Ryan turned 54 shortly after winning the Super Bowl with the 1985 Bears, a team that featured the greatest defense in history.

Ryan was combative, bombastic and did not trust inexperienced players. He refused to play Mike Singletary, a second-round pick in 1981, prompting former Chicago general manager Jim Finks to overrule his defensive coordinator.

When Ryan informed Singletary that he was earning his first career start against the high-flying San Diego Chargers, Singletary gushed with gratitude. Ryan quickly shut him down.

![Remembering when Buddy Ryan punched fellow coach Kevin Gilbride on the sideline [oembed : 86497146] [oembed : 86497146] [oembed : 86497146] [oembed : 86497146]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

“Buddy looked at him and said, ‘Don’t thank me. Thank that bleeping general manager. I wouldn’t have you on the field,’” Plank said.

Nevertheless, Singletary was so excited that he invited his entire family to the game.

After the first play from scrimmage, Chargers quarterback Dan Fouts went to a no-huddle offense, rushing his team back to the line of scrimmage. According to Plank, a confused Singletary called timeout, having little experience with defending the hurry-up offense.

Ryan: “Hey, who called timeout?”

Singletary: “I did, Coach. They came out and lined up to run a play without a huddle.”

Ryan: “Sit your ass on the bench.”

And that was that. Singletary’s first start as a Hall of Fame middle linebacker lasted one play.

“I remember he didn’t like rookies,” Plank said. “And he didn’t like cowards.”

Like Arians, Ryan enjoyed a quality beverage. After games, Arians prefers Crown Royal in a Styrofoam cup. Ryan preferred to sip Dewar’s from a Gatorade cup.

Unlike Arians, Ryan was also proof that some coordinators do not make good head coaches. While Ryan had success in Philadelphia, he was a one-sided coach, a brilliant defensive strategist who knew how to rally that side of the room. But for whatever reason, he never connected with the offense, probably because he thought it was overrated.

Just before his last head-coaching job, Ryan spent one season in Houston, as defensive coordinator of the Oilers. That season, he drew headlines for punching the offensive coordinator, Kevin Gilbride, during the heat of a game.

Before the season started, I showed up at their training camp facility in San Antonio for a mid-afternoon interview. Ryan was dressed in pajamas and was just finishing his siesta. That’s when I knew he’d lost his edge.

The following year, Ryan brought a monsoon of interest and chaos to the desert. He was the bold stroke the bumbling franchise badly needed, and if you want to gauge his early impact, check out the following 1994 passage from Sports Illustrated:

“Spring, 1994. Phoenix. Cardinal season-ticket sales have nearly doubled. Already. The Pro Bowl punter has been cut, the ’93 first-round draft pick has been ripped, three former Pro Bowlers have been signed as free agents. Already. Two of Buddy Ryan’s sons, Rob and Rex, have been named assistant coaches. Defensive lineman Eric Swann has taken swings at teammates on each day of a three-day mini-camp…”

There was never a dull moment with Buddy, and his stint in Arizona was no different, even if the results were lacking. He finished 55-55 in his career as head coach.

But he was a monstrously talented defensive coordinator with the ability to extract absurd and endearing loyalty from his players. He appealed to a certain kind of player, those who live to inflict pain. He had a rule after every interception. He wanted the 10 blockers to all go after the quarterback.

Oh, and he was carried off the field in New Orleans, by players who would’ve run through a brick wall for their beloved Buddy.

“That story says it all,” Plank said. “You really don’t need to say anything else.”

Indeed.

Dan Bickley writes for the Arizona Republic, part of the USA TODAY NETWORK.

![Buddy Ryan dies at 82 [video : 86462054]](http://videos.usatoday.net/Brightcove2/29906170001/2016/06/29906170001_5001939604001_5001950813001-vs.jpg?pubId=29906170001)

![Buddy Ryan through the years [gallery : 86460384]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/4d7fdeed70a738301f73223a6713b174a12434f2/c=0-234-1700-1687/local/-/media/2016/06/28/USATODAY/USATODAY/636026985116754770-BUDDY-RYAN-G1FORBE12-4C-223313.JPG)