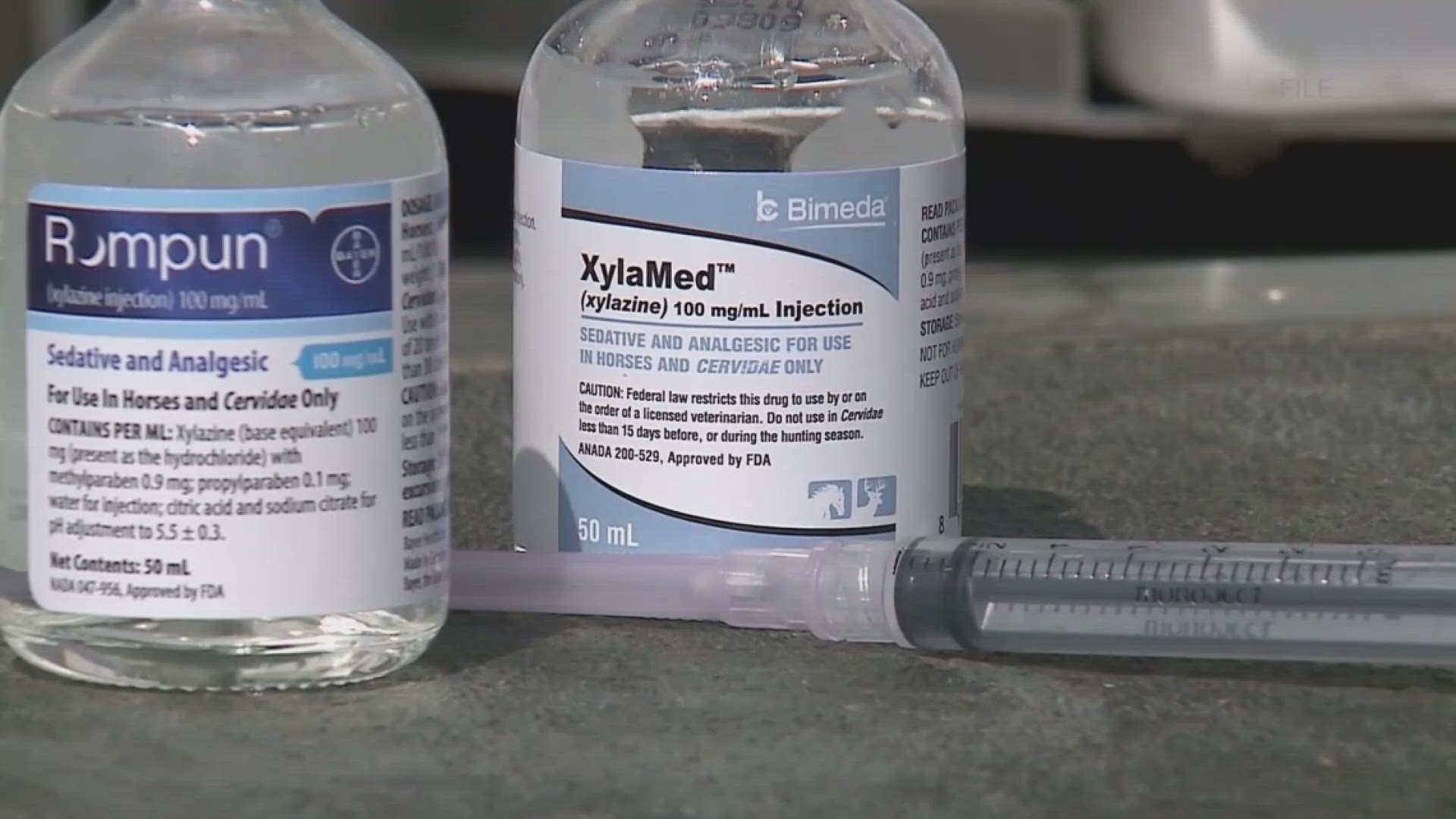

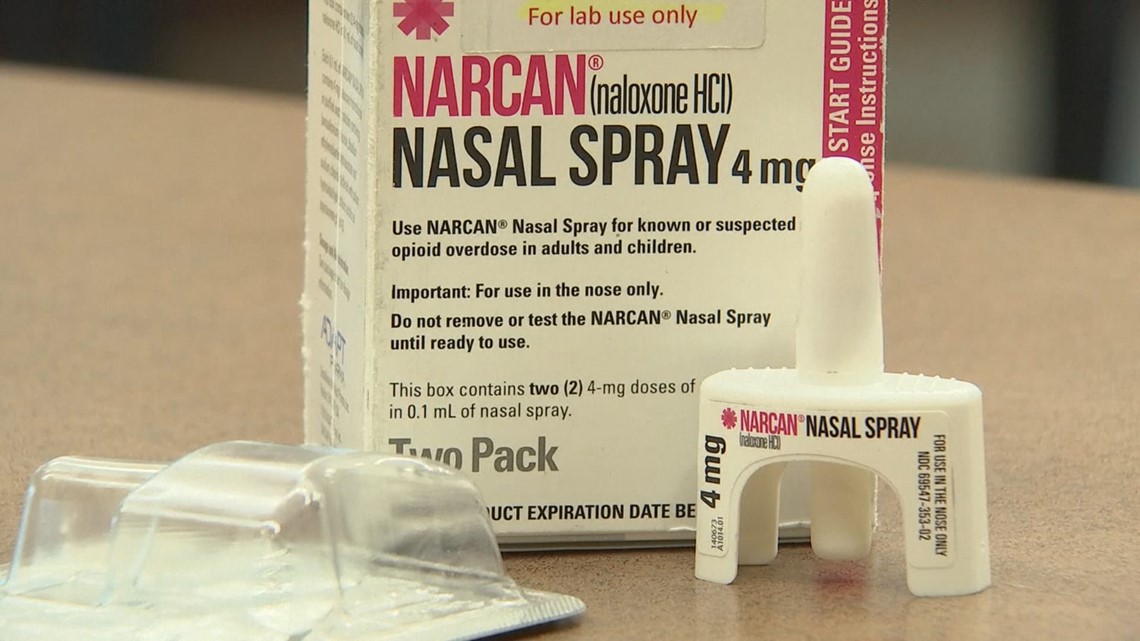

NEW YORK — Naloxone, a medication that can reverse opioid overdoses and save the lives of people who use drugs, doesn't work on xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer that White House officials have labeled an "emerging threat" in the illicit drug supply.

That's because naloxone — also known by the brand name Narcan — is just not formulated to work on xylazine, which is a powerful sedative, not an opioid.

Amy Werremeyer, the chair of the department of pharmacy practice at North Dakota State University, told CBS News that expecting naloxone to work on xylazine is akin to putting a star-shaped peg in a round hole.

"They're going to land and fit into the brain in two completely different spots," said Werremeyer, who is a licensed pharmacist who studies opioid and substance use.

Opioids bind to certain parts of the brain, called mu receptors. There, they activate, causing the high associated with opioid use. However, opioids can cause respiratory depression, which means the person can stop breathing. This is the cause of most overdose deaths, explained Claire Zagorski, a chemist, paramedic and translational scientist in Austin, Texas, who studies xylazine. Naloxone removes the opioid from the receptor, reversing the high and other symptoms.

"Naloxone gets to sit there instead of opioid sitting there, and so that's how it reverses the negative effects of an opioid," Werremeyer explained. "It makes it so that literally the opioid can't get to where it's trying to reach. Xylazine is trying to reach a completely different landing spot in the brain where naloxone doesn't have any affinity."

But if the drug isn't an opioid, Zagorski said, "Naloxone wouldn't do anything to the drug in your body. But that's also not really meaningful because it's not meant to."

What works when reversing an overdose involving xylazine?

An important thing to remember, experts said, is that xylazine is rarely used alone, and Zagorski said there's no reportable data about overdoses that occurred in people only using xylazine. Instead, the sedative is often used alongside opioids like fentanyl or heroin. People who use drugs may not know that there is xylazine in the substances they are taking.

The Drug Enforcement Administration said in March that nearly a quarter of powdered fentanyl it tested in 2022 had xylazine mixed in. The DEA said it had seized mixtures of the two drugs from 48 of the 50 states, and a Philadelphia-based harm reduction organization told CBS News last month that about 90% of the city's drug supply was tainted with xylazine.

"It is not unusual for a sample obtained on the street to have between three to 10 different substances, with xylazine being one," said Anita Jacobson, a pharmacist and clinical professor at the University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy. "Sometimes it's the majority of the sample, but usually (xylazine) is a small or trace component."

Because xylazine is so commonly used with opioids, experts said it's still good to give naloxone — which will soon be available for over-the-counter purchase nationwide, and is currently available in most pharmacies or from public health agencies — to someone who appears to be experiencing an overdose. Jacobson said that naloxone is unlikely to have negative effects if given to someone not experiencing an opioid overdose, so if you are a bystander to an overdose and don't know what substances were used, it's better to use naloxone than not.

"The naloxone will still work on everything that's an opioid," said Jacobson. "Any opioid will be reversed, and breathing will be restored, but they may still be sedated, because xylazine is a sedative and its effects are not reversed. Responding to an overdose has changed in that regard. People may not wake up when they're given naloxone, but it will restore their breathing. The focus should be 'Are they breathing normally?'"

Experts still recommend staying with the person and calling for help if able.

Could scientists develop a reversal drug for xylazine?

There are currently no naloxone-like reversal agents for xylazine. On April 12, Dr. Rahul Gupta, the director of Office of National Drug Control Policy, said that he is requesting $11 million to develop a strategy to tackle the drug's spread. Plans to do so include developing an antidote.

Zagorski said that there has been "a lot of discussion" around developing such a product, but said she is not aware of any "formal work" being done. She also expressed some skepticism about creating a reversal agent for xylazine, because some research has showed that reversing the drug's effects could cause rebound hypertension, or a sudden spike in blood pressure that can occur when a person suddenly stops using a substance. Because of this, Zagorski said, a reversal agent could be "really risky," especially if the goal is to develop something like naloxone that can be used by the general public in non-clinical settings.

"That's kind of a frustrating feature of xylazine working in this particular domain of the body. ... It clicks similar receptors to adrenaline," Zagorski said. "It becomes really easy, unfortunately, to swing too wide in the other direction and get to a point where your blood pressure is really, really high, and that can be very dangerous. This is a hairier question than it was for fentanyl and other opioids."

There are some medications that have been used to reverse xylazine's effects in animals, Zagorski said, but it would take significant time and research to make sure that those medications could be used in humans. One drug has been approved for human use, but only in neonates, so researchers would still need to determine dosages for grown adults.

However, because xylazine does not stop breathing the same way opioids do, Zagorski said there may not be a need for a reversal agent.

"The thing that really kills people with fentanyl and other opioids is that they very suddenly stop breathing, and with xylazine there just doesn't seem to be the same immediate, acute risk to life that we see with potent opioids," she said. "That's not to say it's a harmless drug. It certainly isn't. But I'm not super convinced, at this point, that we really need an emergency rescue drug that we can put out to the community, especially since there are so many downsides to the possible drugs we have right now."