You've seen some of them on the covers of bestsellers and on television talk shows.

Now, a coalition of the nation's pastors is coming together to fight escalating racial violence in the United States. As they have watched events unfold in places from Charleston, S.C., to Ferguson, Mo., and from Staten Island, N.Y., to Los Angeles, what struck them was that there are practices and methods used by churches that they felt could help. They are trying to figure out ways to fix what they call disunity in the country.

"I don't think it's just race but a racial divide that's amplified by way of access," says Bishop Harry Jackson, co-founder of The Reconciled Church and senior pastor at Hope Christian Church in Beltsville, Md.

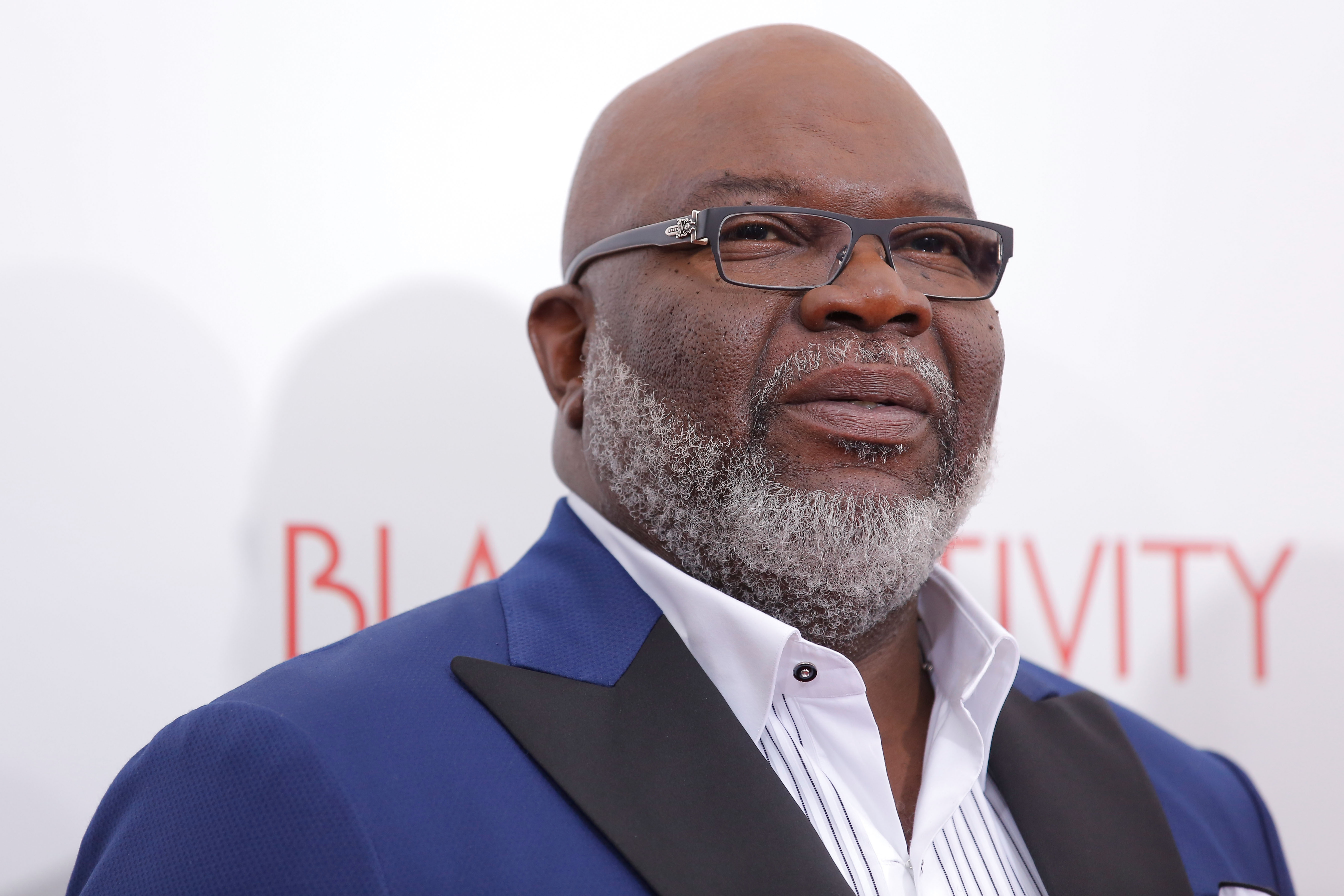

The Reconciled Church is an organization headed by Jackson, Bishop T.D. Jakes of The Potter's House megachurch in Dallas and James Robison, founder and president of Life Outreach International in Fort Worth, Texas. The group wants to figure out the best ways to heal America's racial divide, publish a book sharing those best practices next year and raise money to replicate them.

Whether it was serendipity or just coincidence, significant dates or meetings connected with the group have come at the same time as major developments in racially tinged cases that have gained prominence since the February 2012 shooting death of Florida teen Trayvon Martin by neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman.

Jackson says the idea first came last year when he attended a religious conference in St. Louis that happened to fall around the same time a grand jury decided not to indict a white police officer in the fatal shooting of black teen Michael Brown in nearby Ferguson. The case and the decision set off waves of protests in metro St. Louis and nationwide.

Jackson, who is black, says there were a number of white pastors at the conference and race was on their minds as they watched the protests.

"Out of it came this idea that there are best practices going on in the church right now that could help heal the great divide," Jackson says.

He reached out to religious leaders in his Rolodex, but the most invested were Jakes and Robison, Jackson said. The men were no strangers to racial violence. In 1967, National Guard troops pointed guns at Jackson as he stepped out on his porch in Cincinnati during riots protesting the conviction of a black man in seven strangling deaths. Jakes' grandfather, the original T.D. Jakes, died in Mississippi after white racists placed barbed wire in the lake where he liked to swim, Jakes said.

"We said to ourselves, 'If we don't spark something to bring healing,' we all had a premonition that the kind of violence that happened this week in Charleston would happen in America sometimes soon," Jackson says. "We felt that if we didn't do our part, there would be race riots in the United States and there would be black and white antagonism and there would be bloodshed."

The group met in January in Dallas, attracting between 150 and 175 religious leaders and 6,000 to 7,000 worshippers, Jackson says. Months later, when the group met in Orlando in April, Baltimore exploded in protests after Freddie Gray, a black man, died in police custody, further solidifying the group's resolve.

The group agreed on seven areas to focus on, or the "Seven Bridges to Peace." They are: prayer and reconciliation events, education reform, civic engagement, community outreach and service, marriage and family, criminal justice reform, and economic development.

Now, the group is grounded and established, with up to 1,000 members of active clergy. The roster includes not only the original three organizers, but also prominent clergy members like Vashti Murphy McKenzie, first female elected bishop with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Miles McPherson, former San Diego Charger and now pastor of The Rock Church in San Diego.

Jakes, who usually uses his words to try to help people motivate and empower themselves, sounds more like an activist when discussing the spate of killings of black Americans in the past two years.

"You hear me speak as a preacher, but I'm also a father and I have three sons," he says. "I have had the talk with my sons about how to respond with police officers."

Jakes believes the real issue is the criminal justice system and differences in how people of color are treated.

"By and large, police officers do an excellent job of protecting us, there are some pockets of poor decision making, poor training and, frankly, just a poor respect for the lives of all people that have led us down a path of trouble," he says. "I also think what's happening in the courtroom is just as much an injustice. When we are tried for the crimes, we are seven times more likely to be incarcerated than people who are not of color, so justice is not blind."

And while the criminal justice system was not a key theme in the initial shooting in Charleston, race was, Jakes says. "It's clear that there was a racial agenda and it's quite clear that this young boy picked up this attitude from somewhere," the bishop said, making reference to "pockets of infectious racism."

The group is studying organizations and efforts that seem to work in terms of reversing racial disparities and the pastors will use their experience at fundraising to raise dollars to replicate these programs, they said. They also want to focus on providing jobs for teens. Additionally, they hope to continue to provide forums so that the ministers can continue to talk to one another, they said, and publish a book sharing best practices in 2016.

The conversations between the ministers are important, Jakes says. "Why should you ask Fox News who I am, or MSNBC or CNN who I am when I live across town? Am I lazy and living off the government or am I trapped?"

The group's next formal gathering is a retreat at the end of August, says Jackson.

He says he hopes Democrats and Republicans begin to talk more about what is going on before the next presidential election. There's an urgency about this, he says.

"It was a burden I couldn't push away," he says.